Interview with Markéta Hejkalová

Writer-in-Residence Markéta Hejkalová in conversation with publisher Bernhard Borovansky.

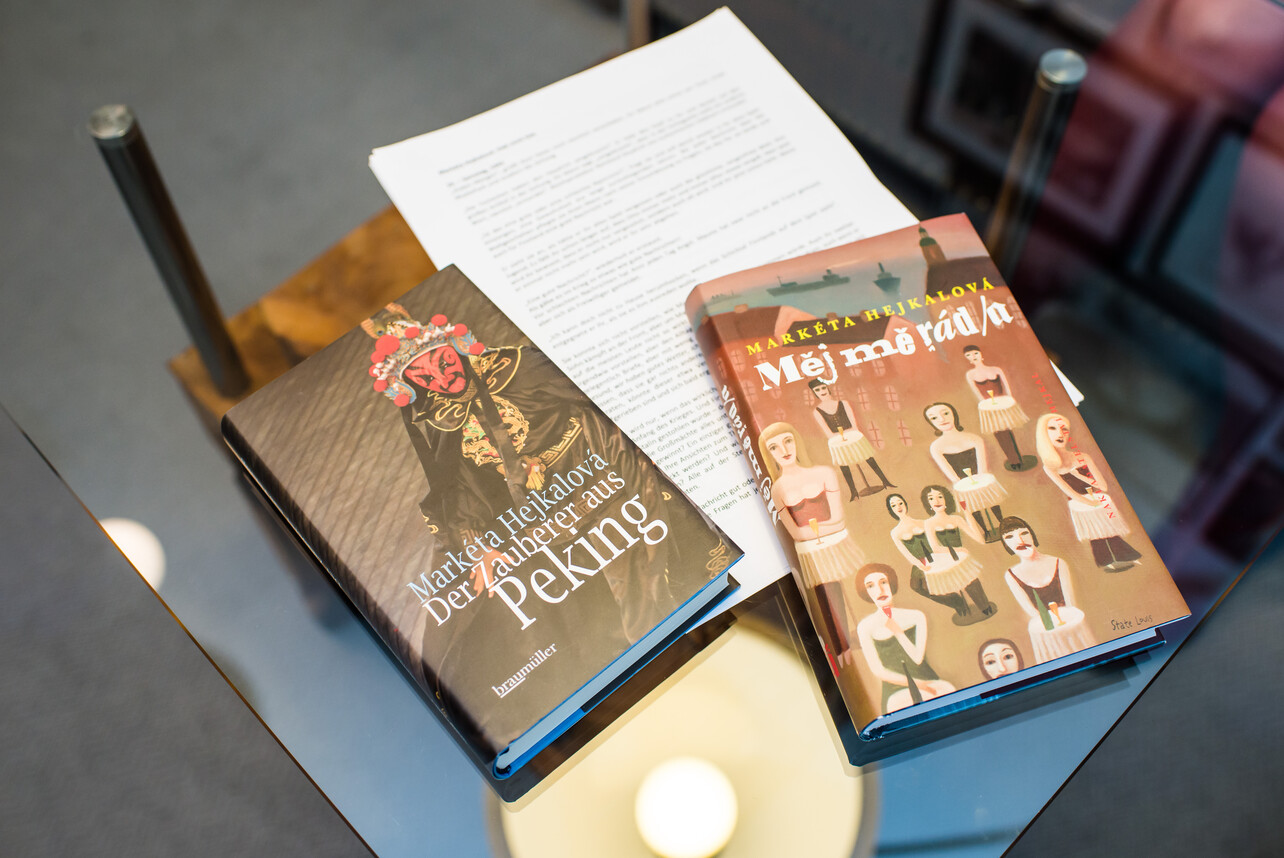

The publisher Bernhard Borovansky conducted an interview with our Q21 Writer-in-Residence Markéta Hejkalová (CZE), who was a guest at the MuseumsQuartier Wien as part of our “Central and Eastern Europe” cooperation with the Austrian Federal Ministry for Europe, Integration and Foreign Affairs. Her book Der Zauberer aus Peking was published by Braumüller, one of the oldest private publishing houses in the German-speaking world. A special focus is on translations from Czech.

Who is a typical Czech author?

Good question, but not easy to answer. Is it Jaroslav Hašek or Bohumil Hrabal? So it is the folk narrators who not only tell funny stories from Czech pubs, but also write about the absurdity of the world and life? Emil Hakl, for example, represents this. Or is Franz Kafka (who wrote in German) a typical Czech author, or Milan Kundera (who writes in French)? Or must it be prose that takes place far from the realism of everyday life, that has its depth, imagination, the grotesque? The best representative of this tradition for me is Jiří Kratochvil. Or is it the “strong woman” Božena Němcová? There are several strong women in contemporary Czech literature, such as Alena Mornštajnová and Kateřina Tučková. Both write about the fates of strong women in the course of history.

What are the themes of Czech literature?

First of all I think, everyday life, present-day life, problems, loving . . . Czech readers like to read about the world they know well. Authors who write about the lives of so-called “ordinary” people are very successful, like Michal Viewegh, for example.

Another big topic is history, the past. Czech-German relations, World War II, communism, collaboration with power, the secret police, freedom . . .

As a third theme I see opening a “window to Europe” for readers, not only to Europe, but to the whole world. That’s also my theme, my books are often set in foreign countries – such as The Magician from Peking in China.

What languages is Czech literature translated into?

Translations are very important for Czech literature, as well as for all literature in the so-called minor languages. I don’t have any current data available, but I think the most important “target language” for us is German, because many Czech authors are translated into German. Hopefully the future will bring even more translations, because the Czech Republic will be the guest country of the Leipzig Book Fair this year and Martin Krafl (former director of the Czech Centre in Vienna and current director of the Czech presentation at the Leipzig Book Fair) is really trying to promote Czech literature in the German-speaking world.

Next perhaps it is Spanish; Miloš Urban or Jiří Kratochvil, for example, have many readers in Spain. And Polish is also important.

English would be the most important language for translations, but translations of Czech authors into English are unfortunately still an exception.

It is interesting to note that there are many translations of Czech literature in the Balkan countries. For them, Prague is still the most important cultural centre, where many intellectuals studied.

My books have been translated into German (The Magician from Peking), Russian, English (but that was non-fiction, a biography of the Finnish author Mika Waltari, who is very popular with us), Bulgarian, Serbian and Albanian.

Which authors have been translated into German?

I know above all the authors who – like me – have been published by the Braumüller Verlag: Jiří Kratochvil, Emil Hakl, Bianca Bellová, Markéta Pilátová. I also think that the German-literature scholar Rake Denemarková is a very popular author in Germany. Also the young Kateřina Tučková has now been translated. I think it depends a lot on the translator, the editor and the publisher. Czech literature is lucky that there is an excellent connoisseur of Czech literature here in Vienna: Dr. Christa Rothmeier, and the excellent Braumüller Verlag.

What are you working on in Vienna?

My two-month stay in the MuseumsQuartier Vienna as Writer-in-Residence had two goals:

First, to write a new novel. Of course, two months is far too short to write an entire novel, but at least I wanted to start on it. And I’m very happy that I was really able to implement my plan – I’ve written 40 pages so far. It’s a family story from my husband’s family. His grandfather founded a grocery store in our small town in 1925 and developed that small shop into a large colonial goods and wholesale business with a coffee-roasting house. It was the best and biggest grocery store in the whole town. In the summer of 1947 the tragedy happened – he had an accident. His car had collided with a train, the accident was his fault. Nothing happened to him, but his wife and 17-year-old daughter died in the accident. About six months later, in February 1948, the communists came to power and took the shop away from him, “nationalised”. But I’m not writing a biography, I’m writing a novel.

The second goal is to promote my novel Měj mě rád/a (Love Me), which was published in the Czech Republic in 2017, and perhaps also to find an Austrian publisher. The novel begins in 1902 and ends in 2017. The focus is on four people – two real and two fictional. The real ones are Lina Heydrich, the widow of Nazi Reich Protector Reinhard Heydrich, who was married to a Finnish theatre director in her second marriage, and Karel Čížek, the communist procurator from the 1950s. I’m looking into the question of what connected these two people? Literature. Lina Heydrich’s Finnish mother-in-law was the famous Finnish children’s author Anni Swan, and Karel Čížek’s mother was also a writer, although not as well-known as Anni Swan. In addition to these two real people there are two fictional characters – my favourite ones: Johanna, who was born into a Czech family in Vienna, married a Czech writer after the First World War and lived with him in Czechoslovakia. In the 1950s her husband was in prison . . . The fourth protagonist is Tereza, a Czech girl who lived in former Yugoslavia and came back to the Czech Republic with her family in the 1990s.

Those were my goals, but now I have also begun to write another, a “Viennese” narrative.

What is your experience of Vienna?

Vienna was never just a city for me, it was a dream of the free world. In the 1970s, in communist Czechoslovakia, I lived in Brno. I knew that Vienna was very close, I watched Viennese television with my parents almost every evening, but I also knew that between Brno and Vienna there was the Iron Curtain, and I didn’t believe that I would ever see Vienna with my own eyes. After the fall of socialism in 1989, fortunately the world changed, and I am very happy and grateful that the Iron Curtain no longer exists – and there are no more borders in Europe.

I am in Vienna to write and work here, but of course I am also interested in the city, especially the Czech traces here. Bohemian cooks who brought Czech dishes and their names to Vienna (for example Liwanzen). The important architect Josef Hoffmann from Brtnice (Pirnitz), near my town, designed many buildings in Vienna, for example Alma Mahler’s and Franz Werfel’s villa on the Hohe Warte, Steinfeldgasse 2. Franz Werfel was also born in Prague.

And I love to simply go for a walk in this city and watch everyday life – in Mariahilf, in Josefstadt, in the surroundings of Servitengasse, where the Braumüller publishing house is located . . . I walk through the streets and alleys, sit in a coffee house, drink a large black coffee and write something.

Which Austrian authors are well-known in the Czech Republic?

I enjoy reading very much, but I am not an expert, so I can only name a few authors whom I enjoy reading myself. Of course the classics: Robert Musil, Hermann Broch, Franz Werfel, Heimito von Doderer. From contemporary literature I know the Nobel Prize winner Elfriede Jelinek, Christine Nöstlinger, Daniel Glattauer, Gerhard Jäger and Josef Haslinger.