"In a way it’s easier to spot a shift in the discourse of a comic strip than of a study."

In cooperation with tranzit.org / ERSTE Foundation, the Romanian visual artist Ana Kun lives and works as Q21 Artist-in-Residence in the MuseumsQuartier Wien in November and December 2021.

Sabine Winkler talked to her about her work on the occasion of Vienna Art Week.

Sabine Winkler: In your work you combine image and text in drawings and zines, dealing with social, political and ecological issues. With this, you reflect upon the multifaceted relationship between image and text; for example, you treat a text as an image, examine the pictorial aspect of characters, their cultural meanings, and so on. How has the relationship between image and text changed through digitalisation?

Ana Kun: I worked as a graphic designer for many years, so by the time I quit my job to become a full-time visual artist I was fed up with the digital medium. I went back to the basics, drawing and writing on paper, switching between the two to get the point across better. By viewing my works online they become more accessible, the text and image are more legible, you have text-to-speech and alt text, but something is always lost – the shared social experience of seeing and talking about art with the person next to you.

You are active in the independent publishing scene in Romania and have already published about twenty zines and books. You have researched visual languages in public space before and after the 1989 revolution in Romania, dealing with graffiti and tags, researching their spectrum of meaning between homage, vandalism and political statement. What insights into local, socio-political and cultural areas can visual languages and communication offer, what subtexts are transported? How does the contemporary visual language in public space differ from that before 1989?

When it comes to (illegal) public writing, things look very different now than they did before the revolution – the texts, although more frequent, are less political now, some are hateful while others humorous, and anonymity is not an issue any more. Now there’s tagging, basically a signature of the author, an “I was here” type of statement. Of course all these differences were brought about by the huge change in people’s relationship to authority and a surge in street arts and activist arts. Most traces of the revolution are still visible in Romania, not because it’s an active subject in the public space, but because of general neglect and poverty. Although we are better with building monuments, sometimes there’s a deliberate intervention to keep the historical traces visible.

In your works you refer on the one hand to objects and figures of Anglo-Saxon pop culture, from chewing gum and kryptonite to Cthulhu and Buffalo Bill, on the other hand you operate in the referential field of Romanian language and culture. How does “global” pop culture and imagery change local ways of life and notions of “the good life”?

It’s odd to see how something in western pop culture becomes appropriated and internalized here, and then reproduced in a range of different flavours. We are still producing the “exotic East European culture”, somehow. Although inescapable, its effects are harder to spot now than it was in the ’90s, when everything brightly coloured and artificially flavoured was considered superior. It led to having a Coca-Cola campaign for 30 years about the “taste of freedom”, mixing the carbonated drink and the ideals of the Romanian Revolution with the “land of the free”, the mythical USA we grew up with. Pop culture is the measure of change, in a way it’s easier to spot a shift in the discourse of a comic strip than of a study.

In 2020 you participated in the online exhibition project Virus Diary by Dan Perjovschi, where drawings were shown daily for seven weeks during the first lockdown. In the lockdown you made work about the current situation and different forms and meanings of isolation.

What does isolation mean to you, or how did you experience this time with its physical distance and digital proximity?

I’ve experienced many types of isolation, some I value, like the one an art residency offers, others I loath, like the first lockdown. However, it had a wonderful spark of solidarity, which lost momentum in the following months. But there was also a great pressure to produce a kind of supportive art that reflects the situation and inspires people to get through. It went back to the basics – what is the purpose of art & artists. On a more general note, it’s probably too early to tell what effect the zoomification has on our psyche.

Where do you think the potential of performativity and visual language in public space lies?

Probably in the seemingly invisible public spaces, like open fields, street corners, vacant plots, urban ruins, sidewalks and so on. There’s great potential in the very nearby and neglected public space we rediscovered last year. Performing outside the centre has its benefits, but it may fail if we don’t understand our neighbourhood and we don’t include our neighbours.

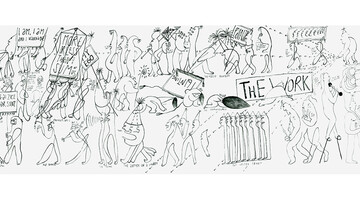

Header Image: Ana Kun, the great procession of artists, drawing on rice paper, 170 x 46 cm, excerpt from the artist book Things are not black x white like in school, Salzburg, 2019.