MQ AiR Matea Kovač on intimacy, visibility and emotion

Croatian animation artist Matea Kovač will be a guest artist-in-residence at the MQ in May in cooperation with the Vienna Shorts film festival. In an interview with Fanny Berghofer, she talks about her work and her new project, which she will open at ASIFAKEIL on 30 May 2025.

During your residency at MQ, you’re planning to collaborate with Ana Maria Maravić on a picture book. How do you envision adapting that project into an animated film?

Since the main characters of the picture book are frogs and their natural habitat is mud and the lake, it felt natural to use clay in the visual expression. Clay is actually Ana Maria’s material and we want to combine it with drawing, which is a medium I feel closer to. During the residency, we want to bring together sculpture and drawing, to find our shared visual language. That’s the first step, and the animated film is a distant step we can only start thinking about once we finish the picture book.

You’ll now be co-creating a film with someone—do you generally prefer collaborative filmmaking, or do you usually work alone?

I prefer to work independently at the beginning of a project, while I'm developing the story, script, and storyboard. But later in production, I enjoy being surrounded by collaborators. On Y, I already worked with Darko Bakliža, who belongs to an older generation of animators, and with my university colleague Kata Gugić. The collaboration with sound designer Vjeran Šalamon was also very important for Y because he had complete freedom in creating the music and sounds, and gave the film a new perspective. Collaboration is a dialogue, and the result of that dialogue are the traces and signatures of other authors within the film. In collaboration, it’s more important to me that the other person’s signature is visible than for everything to be completely aligned.

Your film Y is an intimate portrayal of a relationship falling apart. Do you see filmmaking as a way to process personal emotions or experiences?

It takes me quite a long time to process personal struggles. When I reflect on emotions, I go deep, I change, question myself and others. All of that takes a lot of time, just like making an animated film. That’s why I find it interesting to connect these two slow processes, as a way to reach some personal insights, while at the same time leaving something tangible behind—materializing emotions. Animation gives me the time I need to process reality. For example, when I write, I come to conclusions and solutions much faster, but with time, those solutions often feel rushed.

Y depicts the complexities of a lesbian relationship. Do you feel that authentic queer representation is still lacking in film—and that portrayals often fall into either idealization or condemnation?

While working on Y, I wasn’t so focused on the lesbian aspect, but more on the universally ironic tragedy—that form is something through which we (as lovers) recognize each other, but also something that later separates us, no matter how hard we try to find a common language. Queer films give viewers space to reflect on gender, sexuality, perception, and identity. But I also believe that films can’t be understood only through what’s “on screen.” It’s important to consider how those films were made, who made them, who funds them, who the audience is (where they come from, their cultural background), how that audience reacts, and what political struggles are happening around and within them.

As a teenager growing up in a very small town during a time when Pride parades in Croatia were met with threats and chants like “kill the faggot,” any queer content meant a huge revolution for me. I remember even finding two sentences in My Name is Red by Orhan Pamuk that I interpreted as erotic tension between two women, though I don’t think that was the author’s intention. I believe that even today, sadly, half the world still holds a threatening stance toward the queer community, and that’s why even less “authentic” content can change someone’s life for the better, can awaken a revolution in them, a desire to fight.

And from the reactions to my film, I can see that people view it differently depending on where they are in the world. To some, it might seem banal, but to others, it might offer something meaningful or helpful.

In today’s political climate, how important is it to center queer narratives in film and animation?

I believe that queer narratives are important, but it’s even more important who tells them, how they’re told, for whom they’re told, and under what conditions. It’s crucial to keep in mind that films not only reflect political systems, they are also a product of those systems.

The Focus theme of Vienna Shorts 2025 is “Move Closer! Radical Intimacy.” What does radical intimacy mean to you—and do you think it’s something we need to explore more through art?

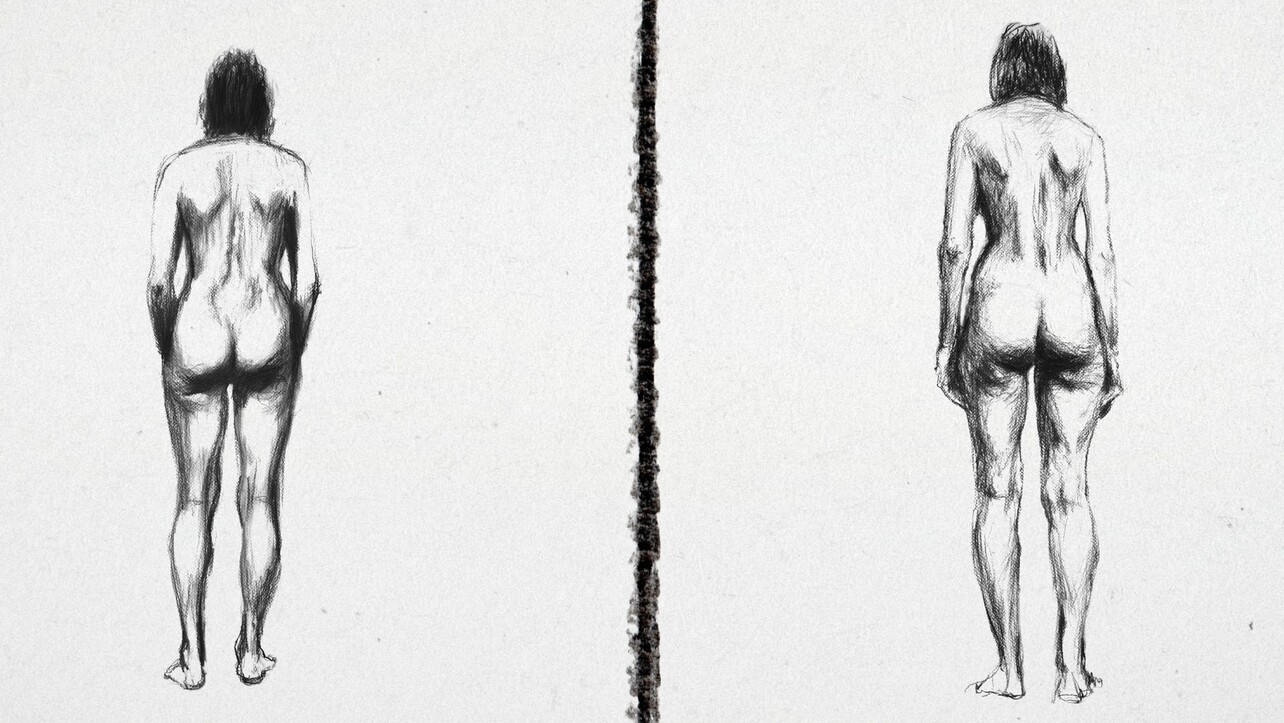

While working on the film Y, radical intimacy for me meant complete exposure on multiple levels; emotional, physical, and intuitive. In addition to directing and animating the film, I also posed nude with my then-girlfriend. I should probably mention that we were going through a breakup at the time, yet it was during that period that we understood each other the most, at least intuitively, because we were seeing the relationship from a new perspective that only art could offer us. Even though we knew the breakup was inevitable, the studio became a space where, for a moment, we created a new shared language. That, for me, is radical intimacy.

Y is a deeply intimate work. How do you approach portraying closeness and vulnerability through the medium of animation?

I would never describe my approach to personal and vulnerable topics as a straight, smooth line. I wrote and rewrote the script for two years, because as much as I wanted to be open, I also wanted to protect myself, to hide from others. And that frustrated me deeply. In the morning I’d write an emotional, honest version, and by evening it would feel pathetic, so I’d write the complete opposite, which then felt cold and distant the next morning. It was all part of a long process. I had to admit to myself what this film meant to me, and it meant a safe space where I had enough time to work through my personal struggles. I had to force myself to forget that this film would be seen by a festival audience, who might judge me based on it. Only when I managed to forget that, I could approach the film with complete openness. I was no longer making it for an audience, but for myself and everything that was hidden inside me at the time.

Can you share a bit about what your next film will be about?

I have a few ideas that deserve my time. It’s hard to say which one I’ll choose because they all carry something personal, but at their core are different themes; from humorous situations to ideas about death, manipulating memory, and so on. I keep wanting to run away from personal and difficult topics, but somehow I always come back to them, no matter how much I try to express them through another medium, like writing.

You also work as a visual effects artist. How does that compare to your work as an independent filmmaker—and do you find a sense of self-expression in helping realize someone else’s vision?

I enjoy working on other people’s projects because even as a visual effects artist, I get the chance to dive into someone else’s world of imagination. It’s interesting to observe how others see the world, and it often happens that they see it in a completely different way, almost like we live in parallel worlds, which mostly makes me happy.

The interview was conducted by Fanny Berghofer, Vienna Shorts.

Veranstaltungstipp:

MQ Artist-in-Residence Matea Kovač & Ana Maria Maravić: Opportune Moment

Opening: Fri 30.05.2025, 16.30h | MQ Raum D

Exhibition duration: 15.05. – 24.08.2025 | ASIFAKEIL | MQ Showrooms

Matea Kovač (b. 1993, Croatia) graduated in Animated Film and New Media from the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb. Her entry into the field of filmmaking is marked by an exploration of various ways to interpret her own emotions and experiences of identity. Through her work, she moves away from conformity, physically materializing her thoughts as a means of self-discovery and introspection.