The collective intelligence of self-organisation

Elisabeth Hajek, artistic director of frei_raum Q21 exhibition space, in conversation with curator Oliver Ressler about the exhibition "Overground Resistance".

Oliver Ressler, born in Knittelfeld, Austria, in 1970, is a filmmaker, artist, curator, and activist who devotes himself to such issues as democracy, migration, economy, forms of civil disobedience, and climate change. Since 2019, he has been working on the research project Barricading the Ice Sheets, funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), which investigates the climate justice movement, the climate crisis, and their relationship to art. For the frei_raum Q21 exhibition space, he curated the Overground Resistance show, which features a selection of artistic works that take various approaches in their exploration of climate activism and the current climate emergency.

Elisabeth Hajek: In the middle of the exhibition space hovers a work by the art and activists group Tools for Action: a cube-shaped sculpture whose metallic surface subtly reflects the light of two large video projections. Its title is Red Line Barricade. On the floor next to the work are stacks of countless posters depicting these air-filled cubes “in action”. What is the significance of these inflatable, light sculptures?

Oliver Ressler: The Tools for Action collective, founded by the artist Artúr van Balen, developed silver cubes for COP21 that were used in public spaces during the demonstrations against that conference in 2015. They can be tossed into the air in a playful manner, thus increasing the visibility of the climate activists. But the cubes can also be utilised as a buffer between police and activists in the case of harassment by law enforcement. All the cubes have a red line drawn across them. A key message of the demonstrations against COP21 in Paris was that we, the people, have to be the ones to draw the red lines, because government leaders, in an unparalleled example of policy failure, have for three decades been unable to introduce the necessary measures to decarbonise the global economy. The posters lying on the floor, which include instructions for making the silver cubes, are available for exhibition visitors to take home with them. This is an open-source artwork, and the adoption and adaptation of this protest technique for specific local demonstrations is expressly encouraged.

One of the two displays positioned diagonally in the immediate vicinity of the work shows the 16-minute film Notre Flamme Des Landes: The Illegal Lighthouse Against an Airport and Its World, by the Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination. Can you briefly explain what this fictitious documentary is about?

This film, by the Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination, focuses on the place where two of its key members, Jay Jordan and Isabelle Frémeaux, live, the ZAD, (zone à defender—the zone to defend) near the French city of Nantes, and evolved from the decades-long battles against the construction of a new airport there. It is the largest autonomous territory in Europe, an experimental site for various forms of living and working together. Most people live there in houses they built themselves according to their own individual ideas. The most spectacular work of architecture there is a lighthouse—far removed from the Atlantic coast. It was erected on the very spot where the airport-development company originally intended to build the control tower. The film shows the construction of this ZAD landmark, which is visible for miles around, and ventures a speculative conclusion: one that depicts the restitution of the lighthouse to this building’s original function as a possibility for the future. The film also shows that resistance is not only the act of blocking the construction of infrastructure that is climate-destructive but is also the act of creation—the building of alternative structures.

Does this mean that the boundaries between art and society/politics are broken down through activism?

In the exhibition Overground Resistance, various approaches are described with which people with a background as artists use their art to become involved in activism. The work of the Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination stands at one pole of this range of possibilities, in which the boundaries between art and politics appear to be completely broken down. However, one should distinguish between the (artistic) work, which is done on-site in the ZAD, and a film that—as an experimental documentation—is naturally a form of representation.

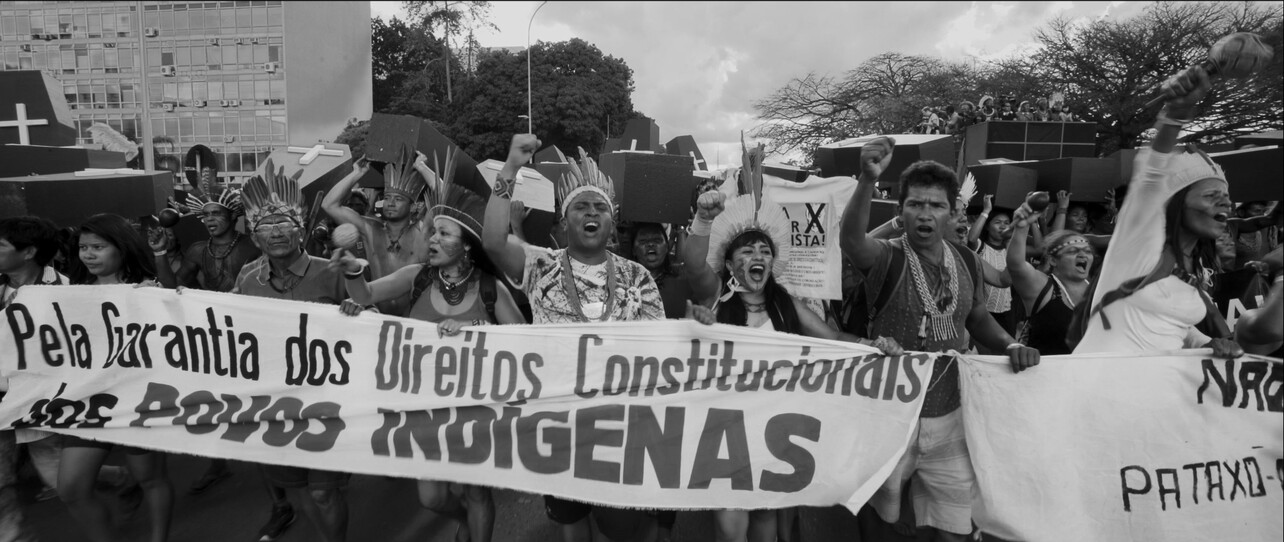

For our exhibition Overground Resistance, you selected twelve international artists who regard themselves as part of the climate justice movement. Four of them are artists from indigenous populations who in their way of life seek a balance with nature. On display is, for example, the audio-visual work Mencer Ni Pewma, by the filmmaker and visual artist Francisco Huichaqueo from the Mapuche indigenous community in Chile. He very closely examines the impact of climate change in his film works and became actively involved in the mass protests against neoliberalism, government abuses, and social inequality in South America. When I saw the film for the first time, the spiritual experiences of the Mapuche filmmaker put me in a kind of dream state.

After all, in Western cultures we have largely lost spiritual consciousness and the ability to experience nature spiritually. Linked to this is a lack of respect for nature and other living things. If one sees the world as an ecological whole based on symbiotic systems, to what extent must we humans exercise restraint in our dualistically formed world and call into question our individualistic culture?

The resistance efforts of indigenous communities to the construction of new infrastructures, which obey the extraction logic, can be regarded as forerunners of the climate justice movement. It was clear to me from the very beginning that the important, active role played by indigenous peoples must also be reflected in the composition of the exhibition. What interests me about Huichaqueo’s film is how he places the genocide against indigenous peoples and ecocide in a direct relationship with each other. In his experimental film, he traces a line of destruction through the invasion by Europeans that began 500 years ago, from an increase of exploitation by capitalism with the murderous, triumphal procession of neoliberalism, which had its beginnings with the putschist Pinochet in Chile, all the way to the potential of a complete annihilation of the majority of life through the overheating of the planet. It goes without saying that such a bleak outlook demands a radical rethinking process, and this rethinking process must encompass all areas of life: how we work, live, and heat our homes; what types of transport we use, how energy is produced, what we eat, and how we communicate with each other. This should also lead to a process of recognition, to becoming aware that we humans are part of nature and not disconnected from it, and that this nature-culture dualism should be challenged.

What new perspectives and ways of interacting with nature can we learn from indigenous cultures?

I believe there is a causal relationship between the current degree of ecological destruction and the West’s capitalist concept of property and ownership. Forms of collectively owned property that cannot be sold by individuals and that has utility for the community have existed for millennia. This indicates a possibility for a relationship to land that is not subject to the logic of the maximisation of profits. And it envisages longer time cycles, as the local community naturally has an interest in passing the collectively managed land down to future generations in an ecologically intact state. I think the climate crisis can be solved only through dismantling existing ownership structures. By this I mean title deeds held by transnational corporations and billionaires—large land holdings, and not the garden of a single-family home.

In many of your own political works, which are usually based on personal relationships to political groups or critical, individual actors, you urgently warn of the consequences of climate change. For the exhibition Overground Resistance, you made a new film, Barricade Cultures of the Future, accompanied by the video Overturn the Present, Barricade the Future. Can you briefly describe what they are about?

These two works differ from all the other films I have made up to this point in that they directly address the role of art in activism. They bring together activists who all have a background as artists and are active in various ways in the climate justice movement. It is my observation that in recent years, many cultural producers have become key figures in social movements; they are in any case much more strongly represented than their corresponding share of the general population. This should come as no surprise, because one role of art seems to be to look beyond the status quo. So it seems logical to form alliances with those social movements that attempt to promote a radical restructuring of society. In the context of Overground Resistance, the two films act as extended curatorial brackets; three of the five featured artists are also represented in the exhibition with their works—either as individuals or as part of collectives.

Climate justice is and will remain a prerequisite for future life. But the connection between economic growth, speculation in the financial market, resource exploitation, social inequality, etc. on the one hand and the climate crisis on the other does not yet seem to receive the attention it urgently needs. Although climate change has now become a central topic of public discussion, we have yet to become sufficiently conscious of the extent of the ecological and social consequences we can expect or climate change’s close ties with racist, sexist, colonial, and authoritarian structures. Are we trapped in an illusion mode and primarily occupied with safeguarding our own comfort zone?

Where does the future of the climate justice movement lie?

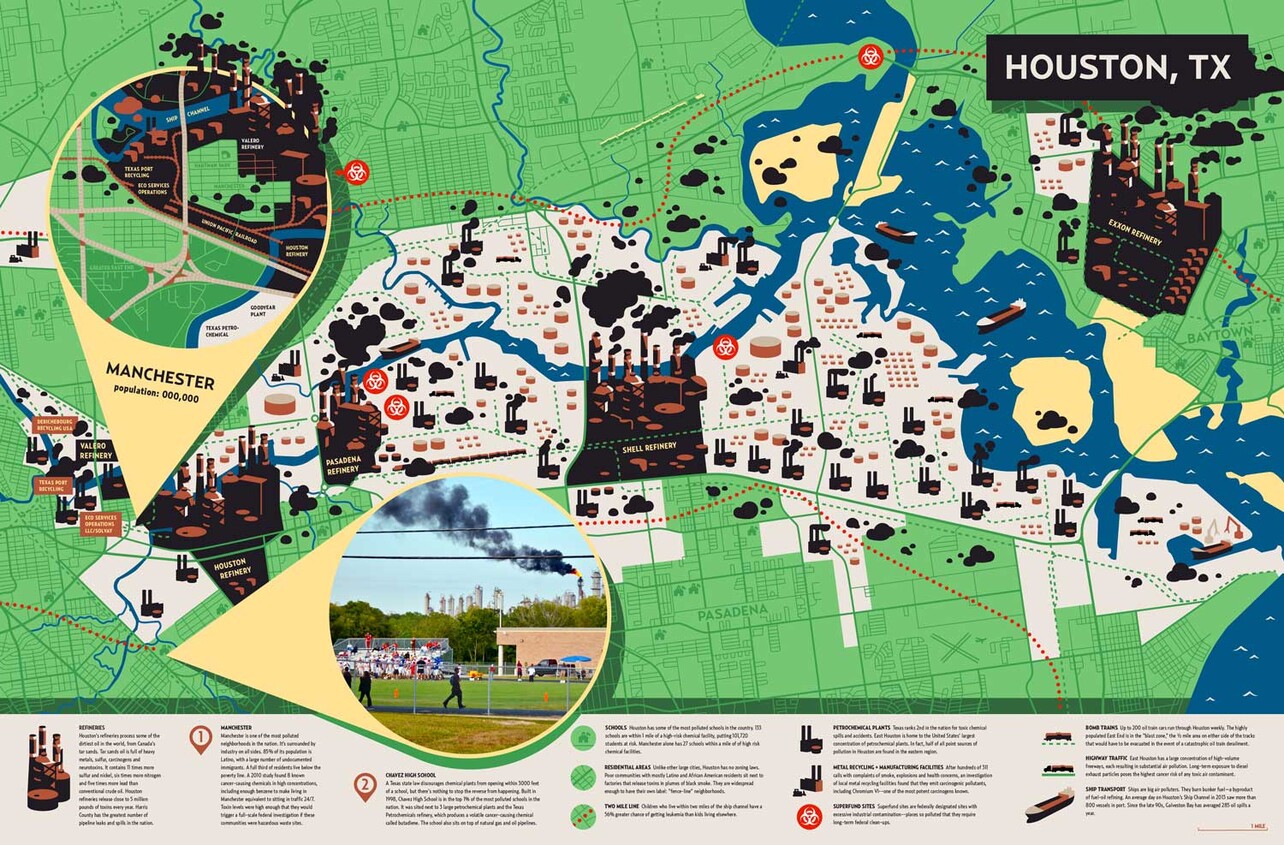

It is unfortunately a fact that those who have contributed least to the climate crisis are forced to bear the brunt of its consequences. And that the majority of the people who live in the very countries that bear the greatest responsibility for the overheating of the planet are most likely to have the means to provide for a comfortable life for themselves for a few more decades, despite climate chaos and an increase in extreme weather events. Perhaps this is part of the explanation for why the media in our part of the world still does not accord the climate crisis the importance that it actually has. Another explanation is that the media is, of course, never neutral or impartial. Media outlets are generally owned by holders of capital who have no interest in seeing the economy massively downsized in a wide variety of areas because that would send their stocks into a tailspin. And the media is also dependent on advertising: if a media outlet were to take a clear stance against the business practices of these corporations that are so destructive for the environment, these companies would quickly stop advertising there. The dependence of the major media outlets on capital is endangering life on this planet. The climate justice movement is well aware of all these things. Although the period before the pandemic saw the largest climate mobilisations in human history, no binding measures were passed regarding decarbonisation, not to mention climate justice. Climate justice movements are faced with the problem of needing to grow larger in order for their voice to be heard by policy-makers, without at the same time abandoning their basic antiracist, antisexist, and anticolonial consensus. The future lies in intersectionality, in collaboration with other progressive actors. This can also work because people on the margins of society are more severely impacted by the climate emergency: the climate crisis reinforces existing inequities—on a global level between different countries as well as within nations.

Since the advent of industrialisation and the beginnings of capitalism, humans have interfered to a massive degree with the cycles of nature. We are now in the midst of an extinction of species of gigantic proportion, and extreme weather events such as heavy rains, hurricane-like wind gusts, heat waves, and flooding are increasingly frequent occurrences. Despite all the political agreements and declarations, worldwide CO2 emissions have not decreased. According to the current report by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the temperature of our planet will have increased by an average of 1.5°C by the year 2030—that is, within only nine years.

How can we, as individuals shaped by capitalism, rid ourselves of the dominance of economic value systems and economic growth as the all-encompassing dogma? How can we find a path to other ways of life?

The climate crisis cannot be resolved through the decision by individual people to free themselves from the exploitation machinery of capitalism. What is necessary is a stepwise dismantling of the system. The largest transnational corporations are also responsible for the majority of CO2 emissions. Aside from privileged people who own houses, individuals are not able to decide how their electricity is produced and how their home is heated in the winter. Large energy companies will always look for large-scale industrial solutions to problems. The obvious solution, which is installing solar cells on every roof—cells that are the property of the inhabitants of the building—cannot be in their interest, because it undermines the foundation of their business: holding a monopoly on energy production. As long as decisions regarding energy supply are driven by the profit motive, as long as the costs of burning of fossil fuels are externalised, there will be no getting away from it. The solutions are all obvious; many of us are aware of the possibility of a resource-efficient existence and would like to have such a life. However, there are power structures in place that oppose these necessary changes. These power structures have to be broken down, and it must be done very, very quickly.

One of the works shown in the group exhibition Overground Resistance is Jonas Staal’s video Climate Propagandas,Video Study. He points out how climate catastrophes and crises are utilised by libertarian, neoliberal, eco-fascist, and conspiracist groups as climate propaganda for their own respective interests. Jonas Staal shows how PayPal founder Peter Thiel in his seasteading project and Elon Musk in his SpaceX project use the climate catastrophe to generate new markets. Survival is becoming a privilege of elite groups. In opposition to this stands the model of the climate justice movement. Is this a portent of the climate-policy battles of the future?

I quite consciously placed the video by Jonas Staal at the beginning of the exhibition because it very clearly highlights key discourses and thus also potential futures but clearly refers to them as propaganda. We will experience very serious social upheavals in the coming years. For me, it is inconceivable that the social order in twenty years will be comparable to the one we know today. The real question is what kind of social upheavals they will be. We will have “degrowth”. The question is whether it is a socially desirable “degrowth” that results in the massive shrinkage of sectors destructive to the climate, like the auto industry, industrial agriculture, the extractive industry, the military, etc., while on the other hand, democratic participation and climate-neutral infrastructures increase. Or whether green capitalism will prevail, leaving existing power and capital interests intact, attempting to use technofixes to contain the temperature increase, and continuing to militarise the borders in the battle against climate refugees from the south, plunging parts of the world into wars and civil wars over land and resources. I think it is clear which future scenario Overground Resistance is taking a stand for.

The fact that more and more people are demonstrating for climate protection and becoming active in climate justice movements shows that they recognise just how dramatic the current situation is. Global solidarity and a collective determination to increase pressure on policy-makers are at the forefront in this regard. Aren’t these efforts to preserve the earth as a habitat for future generations coming too late? Can we still succeed in bringing about an environmental turnaround through a drastic and rapid reduction of greenhouse gas emissions?

It is clear that temperatures will continue to rise, even in the unlikely case that we succeed within a very few years in bringing about global decarbonisation. The amount of greenhouse gases that has already been emitted into the atmosphere is simply too great, and these are gases that will continue to be active for decades. But this doesn’t mean that it’s too late to act. Every additional year of inactivity destroys the basis of life for millions of additional people, beginning in the southern regions of the world. Non-action on the part of the wealthy countries is an expression of climate racism.

Is there anything that nonetheless gives you reason for optimism?

As long as there are opportunities for taking action, one must act. Government responses to the pandemic have shown that the unimaginable can be made possible: the economy was shut down.

My activities are driven by the insatiable desire to see fossil capitalism collapse. I close my eyes and see cities before me in which automobile traffic has been banished and public spaces have been reclaimed for walking, talking, playing, and cycling. I long for the day when the billionaires are expropriated and their money pumped into the creation of climate-neutral infrastructure in the South. I have faith in the collective intelligence of humans that in emergency situations they will self-organise and take a stand for life and against destruction.

Header image: Rachel Schragis,Confront the Climate, flowchart, 2016