The Artist Edgar Honetschläger in Conversation with Curator Marcello Farabegoli

Interview on the occasion of the exhibition "Japan Unlimited" at frei_raum Q21 exhibition space.

Marcello Farabegoli: I had the pleasure of meeting you in Trieste in 2014, where I was presenting you at the Salotto Vienna. We talked about your monumental film Los Feliz, in which your gigantic paintings merge with classical film. At that time you spoke of the power of the image.

Edgar Honetschläger: oh god, one could write a book about it. but briefly: the film LOS FELIZ uses moving paintings to connect ROME with LOS ANGELES – the two most important centres of manipulation. for centuries the catholic church had the greatest influence on the people by commissioning artists to turn its message/mission into breathtaking pictures, in the 20th century HOLLYWOOD assumed this role. america manipulates the world primarily through its film industry = images. the protagonists of LOS FELIZ are the devil, the japanese princess of grass (shinto), and a young lady who wants to become famous. together they drive through a fictitious, painted and drawn AMERICA – a seven-day journey, like the genesis. a monstrous panoramic machine was created, on which pictures (13x51 feet), which i’d painted in japanese ink, pass in a loop – in front of it a 1950s mercedes is parked with the actors on board. it is not the car that moves but the landscape behind it, therefore the illusion is being created that the car is driving. this artificial world is driven by three cardinals standing on each others’ shoulders and turning a crank that moves the paintings/the world. when the three protagonists get out of the car, they find themselves in a completely drawn ambience – from a gas station to the restaurant etc. this is how the first road movie shot in a studio was created over a time span of 14 years (!).

www.losfeliz.at

How old were you when you went to Japan and why did you go there?

i was in my late twenties. before that i had been living in NEW YORK CITY for four years . in 1991, when the second gulf war started the mood in manhattan was scary. with friends i set out for washington DC in order to join rallies against the war. it was the time of the economic bubble in japan. nippon believed that it could outdo america economically, japanese companies bought up important american symbols like the empire state building, columbia studios, which were then renamed as sony etc.; as a consequence there was serious japan bashing in american politics as well as in the media. but in manhattan more and more japanese galleries, art dealers popped up etc. one of them discovered my work and said: “you deal with space like a japanese, it’s so close to our aesthetic feelings, you should go to japan.” completely turned off by the US because of the political arrogance I borrowed money from a friend to pay for the flight to japan. when i arrived something strange happened. at NARITA airport i felt like i was at home. a feeling i hadn’t known before, because i’d never felt at home in austria. i’ve never felt at home anywhere. i don’t trust people who claim to love their homeland. what’s that supposed to be? the concept of nation, which occurs very late in the history of mankind, needs to be rejected, because it’s dangerous. we should only differentiate in cultures. some cultures one feels closer to. from the very beginning i’ve felt very close to japan, and that’s how it has remained to this day.

Why did you stay there so long? What “trapped” you there apart from love? But what bothered you there the most?

it wasn’t a love affair that led me to japan. after the harshness of NY, tokyo felt like a soft cushion. it was so wonderfully warm, wonderful people. i couldn’t get enough of it. the first four years there were among the most beautiful of my life. then a number of things began to go sour, because the cake is small, you come from outside and want a piece of it. whoo – then it can get cynical and harsh in tokyo, too. but i didn’t feel i had learned enough, so i stayed on. for eight years i studied literature, history, politics, culture and the natural world of japan – autodidactically. all that flowed into my work and i started making movies for the cinema. tokyo had become my home base. as i was going to the US, europe, south america regularly i’d find confirmation again and again that japan was nevertheless the best place for me. after all tokyo turned out to be 20 years the centre of my life – but owing to the constant travelling i really spent 12 years there. nothing there really bothered me, as i realized pretty fast that any culture one dives into needs submission to the cultural givens, adaption to the local circumstances and constant learning. perhaps one could rather say that while being there i missed certain things like the western discourse culture. in japan, intellectuals know what their colleagues, what competition is doing, but there is no direct confrontation. as a european, i found that difficult, because many ideas arise through conversation.

Your works – especially your paintings and watercolours – somehow seem “Japanese”. Is it really like that or was it always like that? Or did your stay in Japan shape you in this way or strengthen your “Japanese” side? And what is this “Japanese” in itself, which has something to do with tenderness, mysteriousness, indirectness or ambiguity?

in western painting, space is created by adding, in the east by omitting. we invented central perspective and are mightily proud of this mathematical principle. in japan, painting has always been flat. on a two-dimensional background, perceiving the illusion of 3D is not innate, it’s a learning process, as i already show in my 2001 film MASACCIO. in japan, on the other hand, one brushstroke on an empty canvas is sufficient and the viewer already gets to see things that are not there. that’s also learned. from my point of view, the space they create is much wider, way more open. in japanese KABUKI, there’s a figure called KUROKO (black child) - a kind of servant, dressed completely in black, who helps the actors on stage. the japanese audience simply doesn’t see him. the art lies in blocking out. or two old men stand leaning on their canes under a blossoming cherry tree, quoting poems about all the beauty in front of them. they do not see the concrete wall behind it and the adjacent parking lot. they block it out, it’s a certain kind of short-sightedness. one only sees what one wants to see. in this respect, i was japanese from childhood on. suggesting is always more beautiful than openly and directly demonstrating. that’s also the beautiful thing about our exhibition, because criticism is never direct – it’s always subtly hidden between the lines. so from the beginning my work was japanese without knowing it, but certain tendencies were of course reinforced by the long stay there.

www.honetschlaeger.com/colors-shorttrilogy

With the term “indirectness”, I naturally have to think of tatemae and honne, which are an essential guide for Japan Unlimited – could you say something about these terms in general? How did you experience them in Japan and how do you deal with them in your artistic work?

i think we know this very well in vienna. what we think and what we say are rather far apart. honne actually means bone – i.e. the truth deep inside. tatemae is what the face shows. it makes life pleasant. in japan you’re not confronted with direct criticism. we know the other side of the coin. in the past, westerners have often said, “these japanese, they always smile, but that’s not honest.” so what? i’d rather live in a society where people are smiling than in one in which everyone scowls and barks at you.

i don’t appreciate art that openly critizises politics. yes, trump sucks, but do i have to show it up front in my art? living as a european in japan isn’t easy, because one is always recognisable at first glance. i never established deeper, more warm-hearted relationships anywhere than in japan, but on the other hand it’s probably the only country where a white european man can get to know what racism means – all it takes is the physiognomy and you’re already marginalised. but it didn’t bother me much, because i’ve always felt like an outsider, no matter where i’ve lived. it’s much better to look at something from the outside than to be a part of it. especially as an artist, one needs to keep distance. my work has a very anthropological approach. it’s preceded by a lot of research. it compares without being judgemental. in its appearance, it is like a pond, beautiful and still, but the pond is deep – you can only understand the depth when you dip your finger into it, more so if you completely dive into it. this has less to do with honne and tatemae than with the fact that i am perhaps playing a game of seduction. the surface draws you in and when you’re ready to go into it, the piece takes you along and literally opens up your eyes and mind.

In 1997 you were represented at Documenta X with your work 97-(13+1), which, to put it very simply, shows photographs of naked Japanese people with chairs. How did this happen and why this piece in particular? And how was it received in Europe and especially in Japan?

in japan, there were no chairs, one sat on tatami mats. the chair introduced by the west dramatically changed both the japanese architecture and the anatomy of the people. when i came to tokyo, most apartments had only one room with chairs, the rest were traditional floors with tatamis. today, that relation has been reversed, often there are no tatamis at all any more. in the past, men had to sit cross-legged, ladies bent on their knees. if you do that from childhood on, it has an influence on how your bones form. in the past, japanese women often were o-legged. today, because of using chairs, they have straight legs like in the west. i was interested in this phenomenon. the chairs for 97-(13+1) came from the streets of new york – the viennese architectural group "the poor boys enterprise" (today “the next enterprise”) had collected 97 of them and sent them to vienna. i took 14 of them and sent them on to tokyo. there i searched for people who in their appearance, character, anatomy and physiognomy corresponded to certain chairs, i asked them to take off their clothes and confronted them with one of the chairs. in shintoism, sexuality is something positive; the primary religion of the japanese is full of symbols that reflect primary gender parts. animism. fertility. women and men bathed together in public baths such as sento or onsen. with the coming of the americans in 1853, the tiresome puritanism sets in – nudity is evil! for a long, long time people resisted it, nudity was considered natural, but the colonialists regarded it as a sign of primitiveness. when i did 97-(13+1), at a time when there was open nudity on TV, many japanese people criticised it sharply. even though the piece had no erotic connotation whatsoever – showing pubic hair is forbidden in japan – still. also, some people in the art scene took offence that i had in part worked with well-known japanese artists. the piece was never shown in japan. in the west, it was very well received. there were no reservations. CATHERINE DAVID, the head of DOCUMENTA X, liked the fact that the fine skin still showed the imprint of the clothes they had been wearing shortly before.

www.honetschlaeger.com/97-13-1

So, now we are slowly approaching your two pieces exhibited at Japan Unlimited. Could you briefly explain to us how the work piece Why is it so hard to accept the void? was created and especially why you’d choose this title, which sounds a bit “zen-like”?

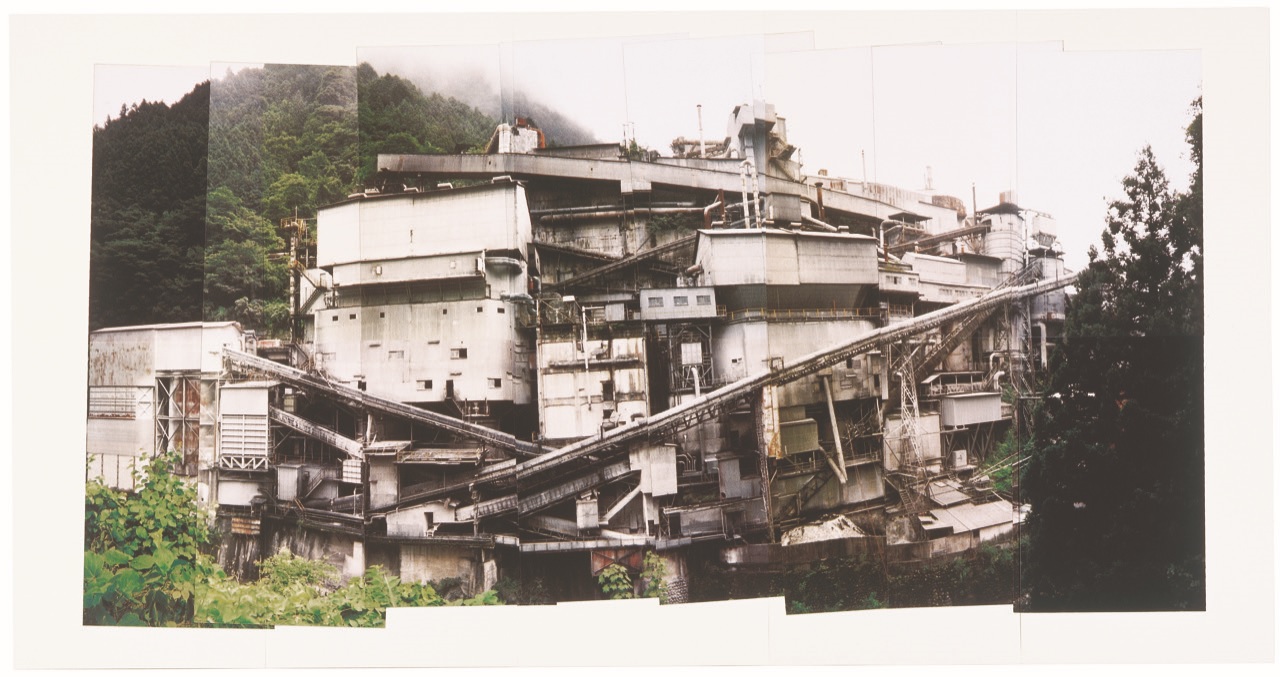

when i lived in america, for years critics would write that i was a pop artist. then, after a few years in japan i was considered a zen master. i have no idea about zen and i was never interested in it. the title simply goes back to the fact that people can’t stand emptiness – they always have to fill it up. in europe, if a bunch of people are sitting together someone always has to talk. silence is inacceptable. in japan, it is/was common to sit together in silence without shame, it wasn’t embarrassing when there were silent/EMPTY moments. with the influence of the west, the urge came to have to fill up. and that’s what this concrete factory looks like. everything is too full. think of a catholic altar, monstrances etc. so much stuff around and then look into the sanctum of a shinto shrine, what do you find there? nothing, emptiness. at best there are sake bottles to be found in there, not because the priests drink so much, but because SAKE purifies . . . 2.5 hours outside of tokyo is a village called OKUTAMA. nearby, built in the middle of the woods, a concrete factory sticks out, i photographed it with a disposable panorama camera, not horizontally but I took eight vertical photos. then i put the photos together, creating a convex effect, and had a ten-part silkscreen print made in munich, which emphasised the deconstruction. everything seems to be wildly thrown into confusion, planlessly built according to the principle “and what else do we need?” CHAOS. at the foot of the factory, which regularly covers all the trees with concrete, there is a river in which there are no fish any more. hobby anglers come from tokyo and fish there, so fish are thrown into the river several times a day – this can be seen in the film L+R.

www.honetschlaeger.com/l-r

At the press conference for the opening of Japan Unlimited you said that your film L+R, and especially the excerpts from the footage you kindly compiled for Japan Unlimited, might be problematic in Japan. I couldn't believe you at the time, but now I'm completely with you. Have you already experienced censorship (on your own body) in Japan or at all?

not open CENSORSHIP but as is so common in japan, non-acceptance, being overlooked. as a foreigner, just like a japanese person, you are simply ignored. in the west, we know this phenomenon in the corporate sector: don’t even ignore – if someone is different, does different things. as in totalitarian regimes, such ostracisms lead to self-censorship, out of fear of non-acceptance. in japanese society the pressure to conform is immense. as a white foreigner, one enjoys a distance, a certain jester’s licence, after all, “we” won the war, but as an asian foreigner in japan, for example, you are usually considered scum. my movie in the JAPAN UNLIMITED show uses raw material from my film essay L+R (2000), but i waved a video of the punk singer FRYING DUTCHMAN (2012) into the film. without reservations this guy screams out all his anger against japanese politics, fantastic. no more TATEMAE. in L+R there is a scene in which the TENNO renounces his divinity. in his book voluntary death in japan maurice pinguet, the french philosopher, writes about this moment when the japanese emperor – forced by the americans – renounces his divinity on the radio. and this moment is disembowelled by western philosophers under the title: it took us until NIETZSCHE – thus centuries – to declare God dead, but the japanese experienced it from one day to the other over the radio! haha. never had they heard the voice of their emperor and then they suddenly got to hear GOD over the ether and he said: i am no longer a god. when i made the film, i tried to find a sound recording of it. we searched for weeks – nothing. and then they told me the emperor had to publish the announcement in a newspaper at the behest of the americans, but he never said it. i found that incredible, so i hired an actor who spoke the words in the inflection and vocal register of the emperor and used it as a voice-over. that didn’t go down well with the conservatives at the presentation of the film in tokyo. you’re not allowed to fool around with the emperor. if you’re japanese you’re in trouble – see ITAMI JUSO (film director), who always railed against the TENNO-SEI (emperor system) and finally paid for it with his life (allegedly suicide).

As you know, the Japanese embassy in Austria suddenly withdrew its recognition for the anniversary year 150 Years Austria-Japan only five weeks after Japan Unlimited was opened and was repeatedly visited by staff from the Japanese embassy. In the rejection, the embassy stated that, on further examination, Japan Unlimited does not correspond to the purpose of anniversary events, which are intended to deepen mutual understanding and promote friendly relations between Austria and Japan. Japan Unlimited has already been visited by about 16,000 people and is very popular. The exhibition together with the Artists-in-Residence of the Q21/MuseumsQuartier and a dense supporting programme will certainly contribute to a deepening of mutual understanding. But is the exhibition really too critical to promote friendship between Austria and Japan? Isn’t “friendship” also based on the possibility of openly talking and discussing negative aspects?

julian schnabel once said that anyone who becomes an artist in order to be loved has chosen the wrong profession – this probably applies to everyone who works in the field of art. we designed the exhibition – as i understood it from the beginning – to be controversial. we wanted a strong reaction and that’s what we got. the whole blah-blah about the 150-year relationship is bullshit. politics does what it wants and we artists are supposed to provide the decoration. the bill hasn’t quite worked out. art can’t be critical enough. it can say anything, it can do anything. its task is to question, to point out, to cut into the flesh. that was already the case with CARAVAGGIO, why should it be any different today? people have always had difficulties with it. the maturity of a society manifests itself in what it can tolerate in terms of self-criticism. every form of nationalism and related censorship must be strictly rejected and fought against, because it leads to absolutism, to dictatorship. so few countries in the world enjoy democracy, and even in those that do we currently have our backs against the wall. art has to shout all the louder. what we show is ultimately harmless, it is subtle, gentle criticism. the affair shows how little it takes.

Doesn't the withdrawal have more to do with the big problems of the Aichi Triennale and the numerous “hate postings” against Japan Unlimited, especially on Twitter, against its renowned artists and meanwhile also against me – recently I was associated with “terrorists of the Red Brigades” and the MuseumsQuartier with the Yakuza?

it has something to do with the ABE administration. right-conservative, like his grandfather, who was also prime minister and realised the nuclear deal with the americans – who would have wanted a nuclear power plant in japan after hiroshima and nagasaki?? the censorship at the recent triennale in AICHI, and of a show in korea just now as well as the reaction to our JAPAN UNLIMITED show, all this can only have been triggered by the government in tokyo. a disgrace – we’ve got democracy around here – artistic freedom – not like in japan. what people in europe don’t know or don’t want to know is that the japanese government passed a homeland protection law in 2011 (FUKUSHIMA went up in march of the year), which makes it impossible for japanese journalists to report on FUKUSHIMA and its horrible consequences. these journalists are being sued for millions. in the worst case, individuals who express themselves on the subject on social media can be put under the charge of a legal guardian, without the right of the family or a lawyer to object. that’s dictatorship. it’s unbelievable that they’re now also trying to influence something that takes place extraterritorially. in comparison to those measures, trying to bend art to their will, which reflects the regime’s fear of truth, is harmless. because the laws that have been implemented, the hiding of the truth, ensure that children and people are dying – in and around FUKUSHIMA and also in tokyo. it’s all so sad and absolutely unacceptable. the government is panic-stricken that its cynicism, its contempt for the people will become public. well, as long as washington covers it, everything is fine . . . the olympic games next year will serve to cover it all up, to make it forgotten. disruptive factors are not wanted. critical pieces in our exhibition are definitely not about criticising japan, the japanese people, they refer to the government who constantly goes against the majority’s will. only 40% of the japanese vote. non-voting is not an issue in japan. it creates advantages for politics. JUDITH BRANDNER makes this clear in her new book about japan – she refers to surveys on what the majority of japanese think about nuclear power etc. which is ruthlessly ignored by politics.

But should we ultimately be grateful to the Japanese embassy for bringing even more attention to our exhibition with this little scandal?

grateful? for a diplomatic faux pas? haha. the embassy only carries out what tokyo orders. they obviously didn’t know how far they were allowed to let us go. that alone is incomprehensible: what is allowed???

Do you think that your artistic work and "Japan Unlimited" could make a small contribution to artistic freedom in Japan?

hardly. but it can initiate a debate that will later have consequences for politics. it can help that JAPAN is not just seen as the culture of outstanding aesthetics and the most incredible food, but to open up western minds in terms of the political system in japan, both in the present and in the past. on the japanese archipelago any reflection from outside is understood as an attack. the islanders are convinced that nobody – except themselves – can understand them. at some point i realised that this is in the interest to both sides – east and west. it is evident that every culture is shaped by an outside and inside view. perhaps reflections from outside are not always equally effective, but over the decades and centuries they leave traces. it’s not unusual for an outside view to be deeply internalised to a point where it is being understood as an unambiguous inside view, in other words as a trademark of a culture. the outside that brought in the element has forgotten or does not even know that it brought it about itself. in the course of time, the original changed so much in the hosting culture as it has been adapted to the local colour to an extent where the original is no longer recognisable. this gives rise to EXOTICISM, because when visiting a foreign culture one will say: “look – how bizarre, it’s weird”, yet one does not even know that the gadget or RITE one observes/discovers in the foreign CULTURE has been invented by one’s own ancestors. globalisation has always existed, it is not a 20th-century invention.