Andrea Palašti: Why look at archives?

Artist-in-Residence Andrea Palašti talks with Sophie Thénault about her works and projects.

Andrea Palašti is an interdisciplinary artist from Serbia whose works focus on photography and film. Her artistic projects such as A Walk Through the Zoo or Sculpture Study: For Bretteldorf are assemblages of archives that develop a discourse on history and our relationship with animals. Andrea has already worked with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC, the Wiener Library in London and the Institute of Contemporary History in Munich. Other than exploring archives around the world, Andrea teaches as well: she was recently appointed as a lecturer at the Academy of Arts of Novi Sad. She was invited by springerin as an Artist-in-Residence at the Q21 in the MuseumsQuartier in Vienna.

Sophie Thénault: You studied photography at the Academy of Arts of Novi Sad, in Serbia, and initially worked as a photographer…

Andrea Palašti: My impatience led me to choose photography as a medium. In a sense, it is a “fast” medium. You push the button and you have the image. And of course, I love it because it is very accessible. While studying I was already interested in exhibition practices, but at the same time I started photographing children’s birthdays and weddings. I was never good at photographing weddings. I always missed the moment of kissing or throwing the bouquet ... I did about three weddings and never got called again.

It really wasn’t for you, then! You also did courses at Atelier Varan about documentary filmmaking?

Yes, those courses and workshops enriched my way of looking at things. They strongly encouraged us to research, to establish a point of view and to interpret reality beyond the usual rules and conventions that we learnt at the academy.

When did you choose to focus on existing archival material?

After the experience at the Ateliers Varan, I slightly changed my perspective and engaged with researches in the framework of the documentary practice and started to work with existing documentary materials from various different archives. I see the significance of working with picture archives as a context to explore alternative narratives. They give us a kind of incidental “school” lesson on history, geography, everyday life, or our culture. Through my projects I try to build up a series of questions and open up a space for thought and knowledge production.

A kind of curatorial practice?

Yes, I collect and display existing materials such as documents and photographs. This research methodology questions memory, subjectivity and identity, as well as the responsibilities of history, but at the same time the responsibility of our “present”. As a lecturer at the Academy of Art in Novi Sad, I encourage students to use appropriation as an important interdisciplinary method to create something by thinking across several different fields like sociology, psychology, history, economics, computer sciences, etc.

In your projects, you use institutional photos from various different archives. You manage to link them with private stories. Do you think those collections tell and show the real story, or just one version of it?

I think it is only through interpretation that we can find a possible meaning in photographs. What has been left out of the picture is in many cases more important than what is pictured. And of course, the same goes for picture archives. They are unstable territories between the past, the present and its futures. It is a contradictory field which opens up a discourse on its own paradoxicality, because their meaning is always set between what is archived and what is not.

So do you think that, as an artist, you can interpret these images completely differently from what they were originally shot or used for?

Depending on the project, but I never go too far from the actual purpose. I’m engaged in researches that concentrate on context specific uses of art, which implies a factor of documentality, so it is important for me to stay close to what I am referencing.

During 2016 you got a fellowship from the Institute of Contemporary History in Munich to conduct a research in different institutions. This project really underlines the idea of photography’s means of constructing and understanding reality.

Yes, within the EHRI fellowship I had the chance to dive into the archives of the Jewish History Museum in Belgrade, the Wiener Library in London, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC and the Bundesarchiv in Koblenz. I explored private photographs that had been taken during the Holocaust by families who went into hiding as tourists abroad. Often using false documents, these Jewish families were buying themselves an apparent safety. The photographs were often made as “happy” snapshots, but only when we find out the context of the image does the contrast between the actual truth and the played out truth increase. A family holiday photo can mean quite the opposite when we discover the circumstances of the image.

A young Jewish girl stands under a sign which reads 'Jews not allowed.' The photograph was taken by a Dutchman, who hid the girl during the war (1941/42).

© USHMM, courtesy of Nederlands Instituut voor Oorlogsdocumentatie

Now, during your Q21 residency, you have chosen to further develop the research about the orang-utan Emil – one of the four animals from your project A Walk Through the Zoo.

A Walk Through the Zoo is actually a lecture performance that follows the lives of four different animals in the Schönbrunn Zoo and its historical contexts. Emil was a former pet of a Serbian civil servant, who was then sold to the Schönbrunn Zoo. He became a media star in the 1930’s and a favourite attraction in the Zoo until he became so obese and depressed that he refused all contact. I also focused on the arrival of the first giraffe, in 1828: she was a diplomatic gift and a political manoeuvre by the Pasha of Egypt Muhammad Ali; the poodle horses – which Napoleon confiscated; and the unlucky polar bear, which was shot dead in 1918 by a soldier because of food shortages. The presentation re-contextualises one part of the picture archive, formed by the former zoo director Otto Antonius, which is today kept in the Historical Documentation Center of Schönbrunn Zoo. The title is borrowed from a guidebook that the Schönbrunn Zoo published as information about a place designed for the visitors’ use.

In this project you refer to John Berger and his piece Why Look at Animals? (2009). He suggests that we look at animals, but forget that they look back at us, just as much. In your installation, we are looking at those apes yet we feel observed, looked at. Was that a goal?

Yes. I wanted to confront the viewer and also to have an ironic set up: a conversation instead of a monologue. Sure, we are looking at them, but we also have to walk past them, and be the subject of their looks too. I also wish to underline the idea of The Human Zoo described by Desmond Morris, who proposed that the unnatural behaviour of animals in zoos could help us understand, accept, or even overcome the stresses that life in consumer societies brings.

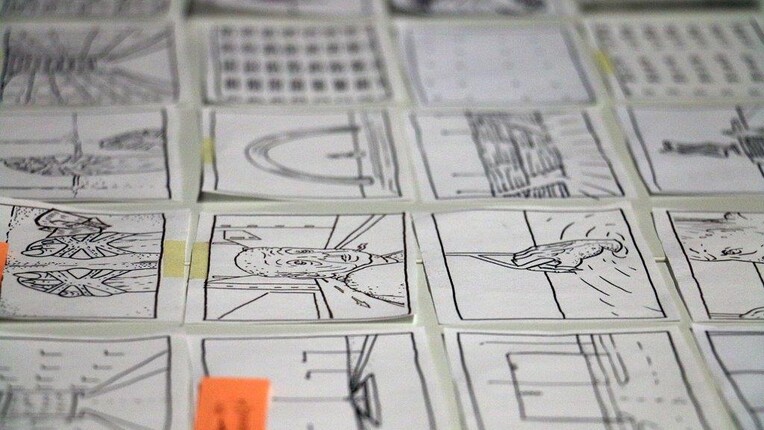

Installation view "A Walk Throught th Zoo" at Artists in Residence BKA/KKA, January 2018, Austria.

© Andrea Palašti

You describe your project as a tier-docufiction. I understand the Tier (animal), and docu parts, but fiction?

Docufiction is a hybrid film genre that combines documentary modes with fiction. In my presentation, I have slightly fictionalised the narrative by reinforcing the documentary materials with fake imagery and autobiographical notes. I do this in order to achieve a dramatic composition.

So, you are fictionalising by means of even more documentation!

Yes! It’s almost ironic. But at the same time, I wanted to make a reference to the German tier-doku-soap TV series called Panda, Gorilla & Co.

Your next project isn´t about animals, but deals with humans: Sculpture Study: For Bretteldorf, which means “board village”. It consists of cardboard sculptures. Can you tell us the story behind it?

It is about Bretteldorf, a wild settlement towards the end of the 19th century in Vienna. On one side of the small sculptures, we can see pictures of flowers and on the other, the cardboard. Bretteldorf It was the centre of a long conflict between the city administration and the inhabitants of Bretteldorf. In 1964, the city of Vienna organised the International Garden Show, which meant the final end for the Bretteldorf settlement. A generous park area, today the Donau Park, was created on the site of the board village.

Your project shows it very well: we have two different views from this event. There is the photography, and the life behind the photography: the cardboard behind your sculptures. You revealed the “real story” behind the official photographs, literally.

Exactly. What I wanted to express is in a way, obvious. Ephemeral cardboard flower monuments for the lost Bretteldorf community. And it was actually made from the photographic documentation of the Vienna International Garden Show, the project that relocated the people from Bretteldorf. I found these pictures in the archive of the Österreichisches Gartenbaumuseum and at the Wiener Stadtgärten.

Your projects seem to stress that there is always a tension between official photos and the reality behind it.

When I work with photographs from different archives, I always tend to think about the official history and the private memory. In my work, I always try to connect these two opposite sides, because both of them make up the “reality”. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t, because private memory is mostly fragmented and dependent on individuals, yet the official history is questionable because it mostly depends on politics.

Now, you are in Vienna. Why do you think this city is important for your works and projects?

My sincere interest in the Vienna cultural scene is the environment that supports research processes in the discourses of collecting and archiving. The fellowships I have taken up here, the KulturKontakt, kulturgemma! at the Volkskundemuseum and the Q21 have also offered me a comprehensive study contemporary art, which is something lacking in my home country due to the lack of infrastructure.

During your residency at the Q21 did you get the chance to extend your search and find new elements, perhaps, for future projects?

Of course! And the best thing was sharing the experiences with fellow residents. Cooking amazing transdisciplinary dishes with Edyta Hul or reconstructing Emil’s skull in 3D with Francesco Pusterla ... The knowledge and information that I was provided with from every artist is of crucial importance for implementing new aspirations in my forthcoming projects. I think these meetings and collaborations are what art is about.

Thank you very much Andrea for this conversation with you!

Interview: Sophie Thénault

Photos: Eva Puella