"We need to remain alert and critical, avoid being instrumentalised by technology, train ourselves to stay on top."

Canadian media artist Luc Courchesne was invited as Q21 Artist-in-Residence in cooperation with SCHAURAUM Angewandte for November 2021. In conversation with Sabine Winkler he discusses his artistic practice.

Sabine Winkler: You have been working with interactive media art since the early 1980s and experimented with immersive systems and spatial experience as early as the 1990s, you are considered one of the pioneers of media art. Issues relating to space and interaction appear in many of your works, increasingly transferred and shifted to virtual space or augmented reality scenarios. Is there a kind of golden thread that goes back to your involvement with exhibition design in the 1970s/80s? What has changed through datafication and virtualisation in the field of art reception since the 1980s?

Luc Courchesne: I always loved going to museums. For the artworks of course, but perhaps more importantly for the experience of their generous spaces, sculpted by light, graciously inhabited by other visitors. And then, once in a while, an artwork captures my attention, opens a door into another world, initiates a revealing “conversation” with the artist. When I practised exhibition design, I challenged myself to construct the complex conditions forming a poetic, inspiring, engaging experience of space in which objects – (artefacts, images, texts, sounds), their positioning to create a path, the light that reveals them, the behaviours they sometimes have – all contribute to this holistic experience of being in the moment. If the virtualisation (digitisation) of spaces and objects breaks the limitations of physicality, opening possibilities such as playing with scale in an infinite expanse and having objects change form, position and relationships to one another, the ambition to create the same engaging human experience in such an unfamiliar setting is a dire challenge.

We are still far from a virtual museological experience equating a physical museum visit. But since technology so deeply reframes our connection to the world, thinking about it, creating and testing scenarios, exposing results, taking note of perceptions and behaviours are necessary endeavours if we want technology to serve human nature rather than the opposite. So the golden thread here is that, if technology has evolved spectacularly, we humans are pretty much still the same as we were millions of years ago, and the important questions we have are as relevant now as they ever were. The only difference is that the tools and processes we have to reflect on them have changed. The most dire challenge for an artist working with technology is to master the current tools and processes in order to create the beautiful simplicity of, say, natural light shining on the marble surface of a Brancusi, in the company of others.

In your work Portrait One from 1990, the virtual portrait of a woman looks at the viewer, poses questions, begins a dialogue, to communicate and interact, moving away from a unilateral active perception and action. In this way, the art object claims agency for itself, detaching from the status of a passive object. What could be a possible perspective from the point of view of artistic works, as assumed in object-oriented ontology?

Astroboy, Pinocchio, or Dr. Frankenstein’s creature are entities that surpassed their fictional creators’ ambitions. Marie in Portrait One, my first interactive conversational work in 1990 is somewhat like that. My intention was to mask interactive technologies – computer controlled laserdisc – by an experience that would be more compelling than the novelty of the tools. I was hoping that a human face, an animated human face, an animated human face seemingly aware of your presence and answering your questions … would do it. And it did, even though there was no intelligence in the programming, only predefined sets of questions from which to choose and steer a “conversation”. The conversional portraits I now make employ real time speech to text recognition, natural language understanding (NLU) and processing (NLP) engines and real time animation of 3D representations of real actors, and finally artificial intelligence (GPT3) to do the same trick: engage human beings in conversation with artificial entities. They does so in a much less constricted way though, and in seemingly natural interaction.

But why do that? The world is demanding us to perform in an increasingly complex technological environment. We need to remain alert and critical, avoid being instrumentalised by technology, train ourselves to stay on top. These biomorphic art projects are perhaps one way of doing just that: stay on top of the game. Thus my current exploration of questions is as old as humankind, the self-aware life form we belong to: Where are we? (Ephemeral Ontologies), and Who are we? (Radical Ontophany). We are still very far from just starting to answer these questions.

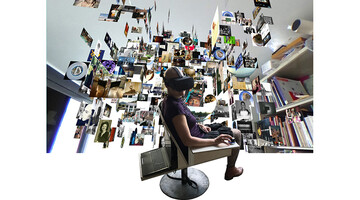

In the various versions of your work Naked in Paradise (2013, 2018), you deal, among other things, with immersive exhibition and archive spaces, with the relationship between real and virtual space. Thus, in the 2013 version, the screens show an extended retrospective of your work on a virtual space and time scale from 1952 to 2052. In addition, the history of media technology over the last 30 years is told in parallel. How does our perceptual perspective change through spatial simulation, what possibilities does it create?

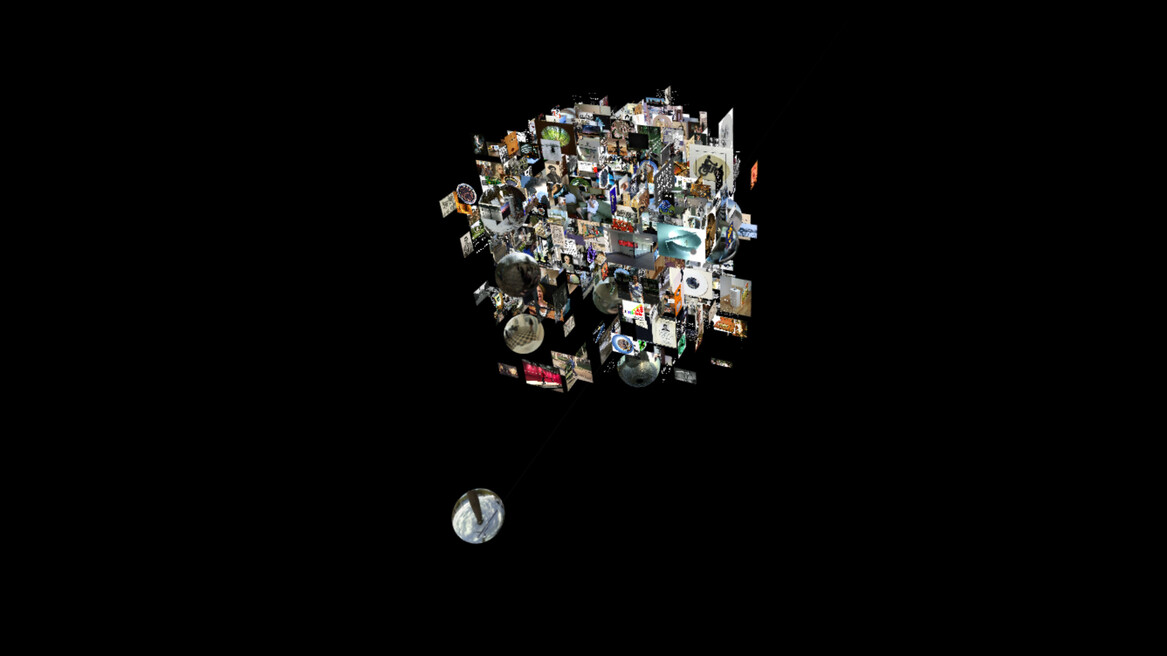

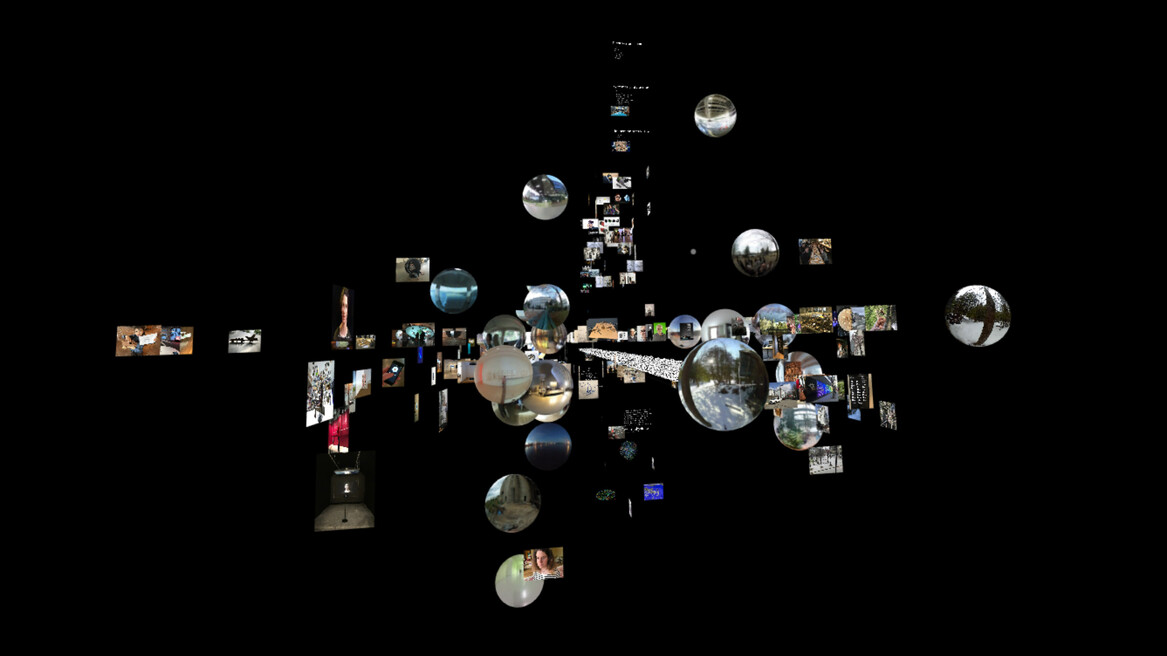

In the 2018 version, the data collection of your works is shown in a VR installation as an archive more or less arbitrarily constructed by the computer. What role does randomness produced by algorithms play in the data collection or presentation of your work?

The concept of embodied cognition points to a process by which our whole body and perceptual apparatus, not only the brain, is at play when we try to make sense of the world. Visiting Vienna, for example, is a richer and more holistic cognitive experience than, say, reading about Vienna or looking at a film or photograph of the city. The same will happen in immersive and interactive artworks inviting us in. With Naked in Paradise, I was curious to “expose” myself in an immersive environment fabricated with my own life and projects archive, to see if it offered novel perspectives on the question of who and where I am. The experience is not yet conclusive but it did help me in developing a holistic conception of things and of the world I live in, its constant transformation, the ephemerality of the models I make, of my posture in this complex set of dynamic relationships.

Historical media (painting, photography, cinema. television) mostly trained us, as in Cartesian science, to frame the world in small discrete parts easier to grasp and understand. To me, the current general interest in immersive media expresses an emerging collective talent to encompass larger concepts for reality, a shared ability to understand the complex systems of interaction of which we are a part, along with other living species and natural elements. Ephemeral Ontology (EO) evolved from Naked in Paradise as an authoring platform to dynamically manage any dataset. The creative challenge in “EO” is now to develop a variety of algorithms to construct, transform and evolve explorable architectures using elements of a given dataset as building blocks. To me, the idea that one dataset can express a diversity of world views, perspectives or, more simply, topographies is relevant today. I find beauty, and perhaps something sublime, in real time transitions from one ontology to another. This is especially the case when ontological algorithms produce models that are randomly evolved or counter-intuitively constructed. Is this out of fear that computer-generated worlds may not always be hospitable to humans?

When space becomes increasingly virtual with computer-generated space, the relationship of the body to space changes. You speak of an ephemeral space and a corpus of information in reference to your work Ephemeral Ontologies. Ephemeral ontologies are algorithmically generated, differ from physical ontologies in their immateriality. Collected data and datasets form the basis for the virtual ontologies that anyone can create for themselves for a moment. How does this work? What new spaces of experience can emerge through the relationships of files or objects to each other?

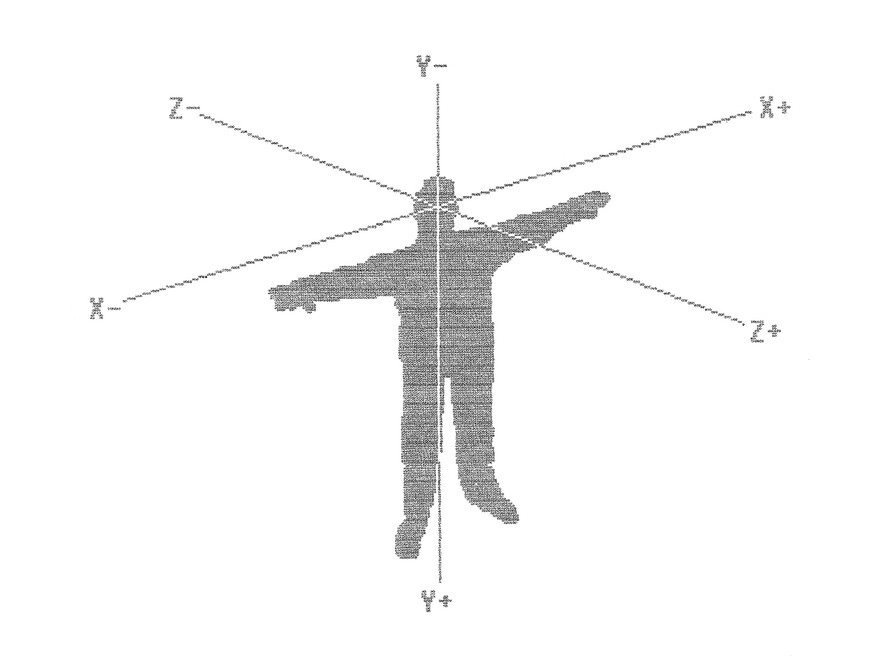

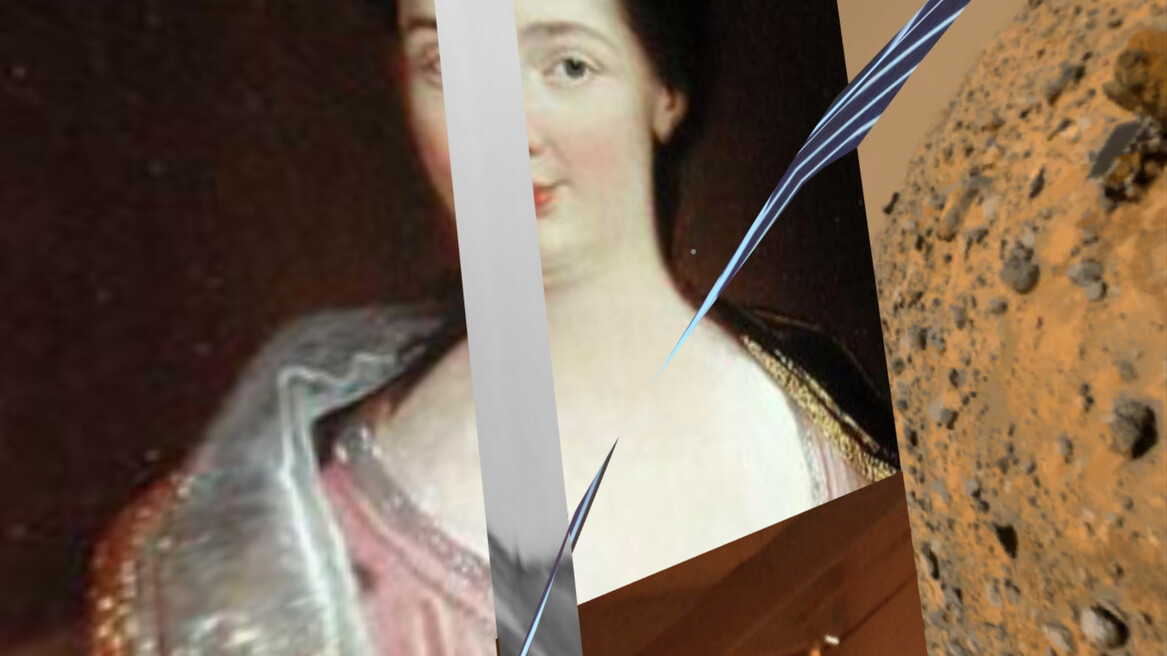

Every art project starts with an ambition. The artist then engages in a process, conceptual and practical, to iteratively implement forms potentially fulfilling this ambition. With the Ephemeral Ontologies cycle of works, I aim to create inspiring explorable spaces exposing the fragility of models for reality, or the subjectivity of belief systems. The process is quite simple: I first collect a quantity of digital assets (images, videos, sound bites, 3D objects, texts…) using the tools I have at hand (photography – framed, spherical – photogrammetry, drawing, sculpture, sound recording…). I then upload these in the Ephemeral Ontologies framework for assembly into a variety of explorable architectures in which I will eventually invite visitors. Each new work in this cycle helps enrich my assets creation toolbox and evolve the processes by which I assemble and transform explorable spaces. Naked in Paradise was the first corpus of assets I used to validate the approach. Wien Chiaroscuro, the work I am initiating in the context of an artist residency at MuseumsQuartier, offers a new occasion to push the concept forward.

Can you briefly explain the concept of the work Wien Chiaroscuro?

The Wien Chiaroscuro project aims to portray the city through interviews of people and visits of the places they inhabit. The stories harvested will connect these people and places (present) with their origins (past) and their expectations (future). I thus have the ambition to poetically expose diverse life trajectories in a chiaroscuro mode, at the frontiers of hopes and fears, of past and future, of light and darkness. This is just a starting point. As the project evolves, I will see where it goes. To me, art making is a journey to an uncertain destination.

Luc Courchesne will present the exhibition Ephemeral Ontologies – Wien Chiaroscuro at SCHAURAUM Angewandte [Angewandte SHOWROOM] at Q21/MQ (26.11.2021 – 11.02.2022).

Image: © Luc Courchesne, Naked in Paradise, 2018