Thomas Sørlie Hansen

Artist-in-Residence Thomas Sørlie Hansen interviewed by Sibylle Vogel and Thomas Kriebaum (KABINETT comic passage)

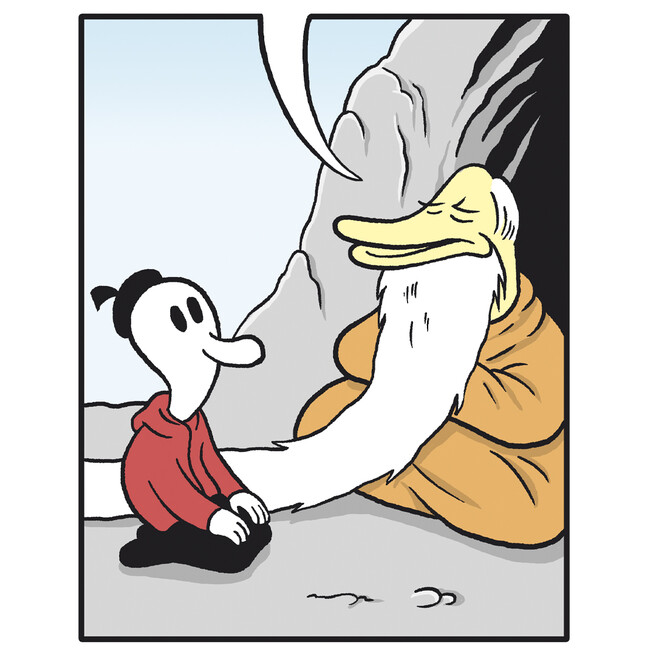

Thomas Sørlie Hansen (37) is a Norwegian artist. He lives and works in Trondheim, where he runs the co-working space OLO, works with visual dissemination of history, and creates comics. His comics are mostly wordless, visual gags in a ‘funny animal’/ligne claire style, with the comic strip ‘Panto’ being the prime example. Thomas was Q21 Artist-in-Residence in October 2020, invited by KABINETT comic passage.

In conversation with Sibylle Vogel and Thomas Kriebaum (curators KABINETT comic passage), he talks about his work and influences and his residency in Vienna.

Thomas, you spent three weeks in Vienna, your stay being a bit impaired by the coronavirus pandemic. However, you made it to Vienna and spent a lot of time wandering about Vienna’s museums. How did Vienna influence your work and comics?

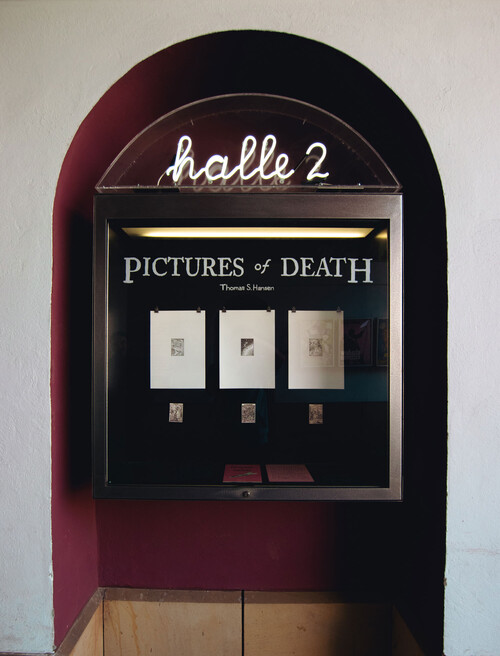

Yes, it was a unique opportunity to be able to see many of Vienna’s museums with little competition from tourists. I discovered that several of the artworks I had referenced working on my booklet Pictures of Death were on display in Vienna, e.g. Death and the Maiden by Hans Baldung Grien. So I guess in a way, Vienna had already influenced me before I visited. It is of course inspiring in itself to visit a city where art, design and culture are so very present everywhere. I have also picked up on the Viennese sense of humour, even though I didn’t always understand every word being said or written, but it’s definitely a blend I can enjoy. It might not be the first thing people notice in my work, but I think sometimes something a bit bleak and twisted comes through.

During your time here, did you get new ideas and find elements, perhaps, for future projects?

Yes, but much of it has not yet manifested. I am always right, however, when I know it is there. It can be a number of small things. For instance, I learned that Klimt always painted his landscapes in a square format and that he never painted the sky in them. That seems very sensible to me. The automatons at the Kunsthistorisches Museum were amazing, so I might make something that moves.

Maybe a comic that moves. Even the cakes and the pastries… maybe something edible could be part of some sort of visual storytelling experience, like some board games that are designed to be played only once. If I were to make a comic that could only be read once, what would it be and why could you only read it once? These things take time to mature, but I am confident I will use inspiration from my Vienna stay in my work.

www.thomashansen.no

Instagram: @taffelhelt

www.kabinett.at

Instagram: @KABINETTpassage

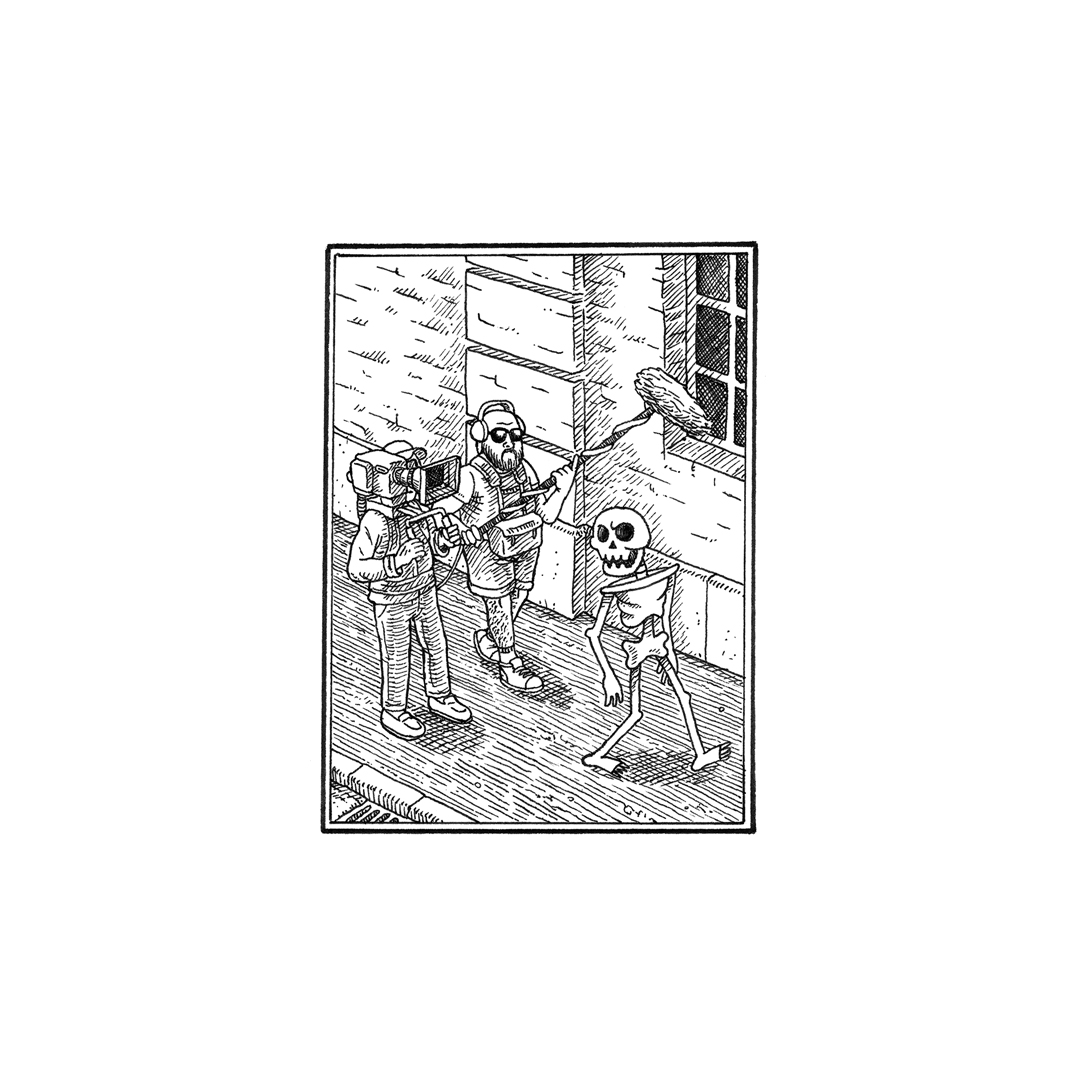

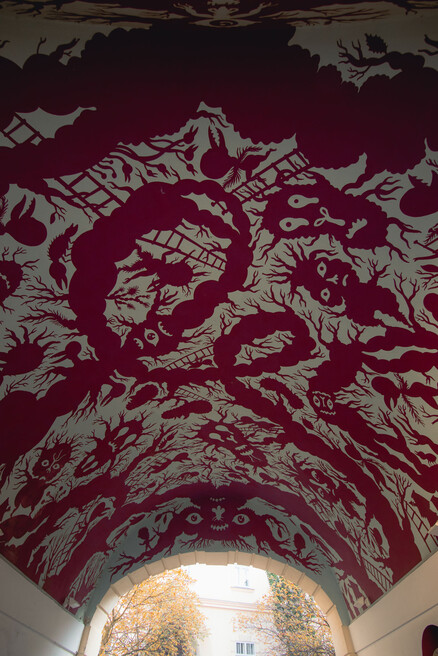

At the opening of your show at KABINETT comic passage, you presented your publication ‘Pictures of Death’ – a homage to Hans Holbein (the Younger) and other artists of the memento mori and Danse Macabre tradition. Can you tell us more about how the idea for this story emerged, personified Death returning to modern times? Why did you choose to present it in the tradition of the Old Masters?

When I started my master‘s degree in design back in 2006, I chose to look at the different imagery we use when we visualise the concept of death or the afterlife. I was interested in this because it is an area of illustration or art where we deal with something mysterious, unknown and unseeable. A topic way too big, of course – the classic mistake. So, it ended up more like a study of social anthropology, with me visiting Día de los Muertos in Mexico, a culture that struck me as having one of the most vibrant visual imageries of death.

On this journey I also came across the European tradition of the Totentanz or Danse Macabre, and I was able to borrow a really old edition of Hans Holbein t.y.‘s well-known series of woodcuts from the 16th century. The tradition had already existed for centuries, but Holbein added storytelling and social criticism and gave it a form that pretty much defined how it could be presented in book form, much like Charles Schultz did with the classic newspaper comic strip. I was captivated by how engaging it still was, 500 years later, and I wanted to make my contribution to the tradition.

The personification of Death in the form of the classic skeletal Grim Reaper is an interesting character of its own. A seemingly European character that goes back centuries, existing alongside religious imagery, but really with more of a secular nature. In Holbein’s time, death was not yet commonly represented as one individual, but rather as a group of skeletons. For me, however, it was natural to represent death as one skeletal figure, like we know him today. There is a lot of funny stuff you can do with such a character, but I wanted this book to be little bit different. Sometimes funny, yes, but also with some social commentary and imagery that can hopefully make a European reader reflect on death today. Originally, Holbein’s prints were presented on single sheets as miniature woodcuts with a description or title in German. These were later replaced by Bible quotes. I wanted to stay as true as possible to the original idea and draw the panels in the tiny size they were printed in by master woodcutter Hans Lützelburger, a stunning 48 x 65 mm, which is something I think few people are aware of. This also represented a technical challenge for me, even though I only used a pen, but it gave me necessary resistance.

Which books, thinkers or ideas have been important in shaping how you think about comics?

I have to mention German illustrator Christoph Niemann, who opened my eyes to what illustration could do back in the early 2000s. He is also a very conceptual illustrator and creates a lot of visual puns with the creative use of symbolry. In my comics, I also strive to tell stories through visual means. I enjoy reading comics that use a lot of dialogue, but somehow it rarely shows up in my comics.

Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics was like a comics bible for me for a long time. Definitely a must read for everyone who works with visual media, and a huge inspiration for me.

The writings on semiotics and art by John Berger have been important to me and my work on a more philosophical level. For instance, he has taught me to be clear and honest about what I am conveying in my comics and to reflect on what’s really happening between the storyteller and the reader.

Finally, the works of Chris Ware and the comics of the early 20th century, by which Ware himself has been inspired very much. These ‘incunables’ of the comics medium are still so fresh and original that they rival anything that’s been done since then. Perhaps it is because they were exploring a new medium, and as pioneers they had to look to other mediums for inspiration or invent something completely new. Krazy Kat by George Herriman is probably my favourite. Reading Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan was an intense experience and made me realise that it is possible to deal with a whole range of emotions in the medium of comics.

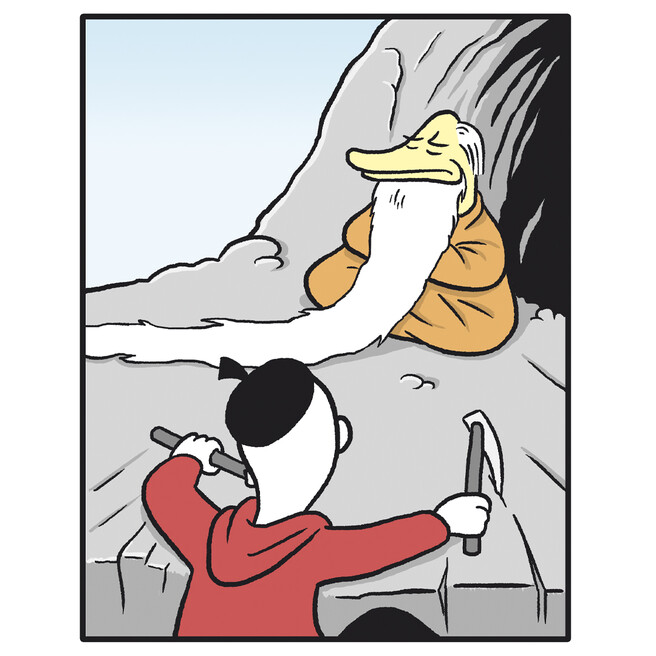

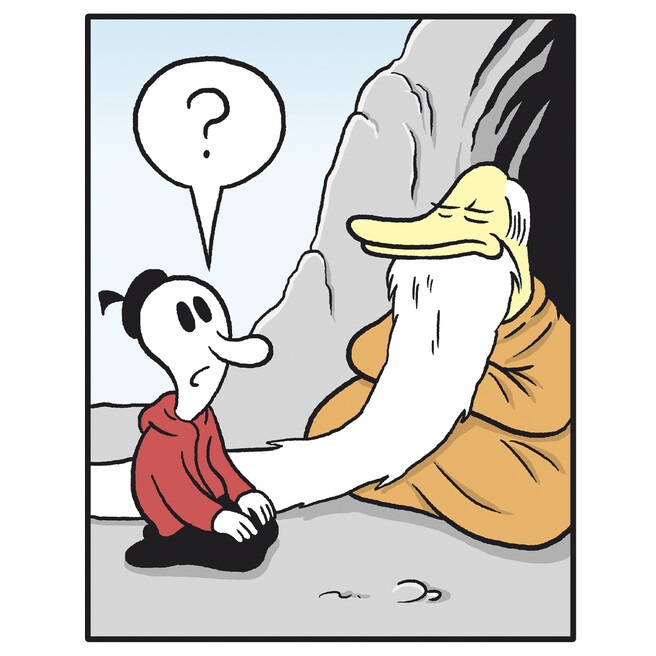

Your comic character ‘Panto’ is experiencing a series of whimsical/philosophical adventures, taking place in a friendly, funny atmosphere. Is there something of yourself in your creation?

I think that is probably unavoidable. In a sense, I feel like he is me or I am him. I also like to ask questions or to question things, and usually things are not what they seem, or they are more complex and nuanced. To many things that have to do with our existence we will never find an answer, so the way I see it, reality is pretty surreal. I feel like there are very few things that are certain. It always makes me sceptical when people are very certain of something. In Panto’s world, this often manifests in the form of optical illusions. I try to surprise the reader in that way. I also take inspiration from my own dreams, and there is often a dream-like logic in Panto.

Although I think it could be interesting to be more aggressive, daring or provocative in my comics, I guess that’s not really me. So, Panto is essentially pretty friendly, but hopefully somewhat thought-provoking and creative.

Does travelling around and being in different locations influence your work?

I am moving around a lot, working in different places and cities. It prevents me from repeating myself too often, I think. And it is great to have the opportunity to see new places and meet new people. It

is a luxury we cannot take for granted and might not be as easy in the future. The pandemic we are facing now is one example.

In general, I think making great art of any kind has more to do with hard work than with anything else. The idea of sitting around, waiting for inspiration to strike, is misguided. But of course you need a mental archive of experiences and visuals to draw upon. You need some fuel for your creativity and seeking out different perspectives is a great way of doing that. But it doesn’t have to be about travelling to some exotic location. It could just be changing where or how you work. This is best in the early stages of any project. When it is time to do the actual work, putting the pen to the paper, I find it is always best to do in the safety of my office in Trondheim.