"I am very impatient. That's why I make these patient films."

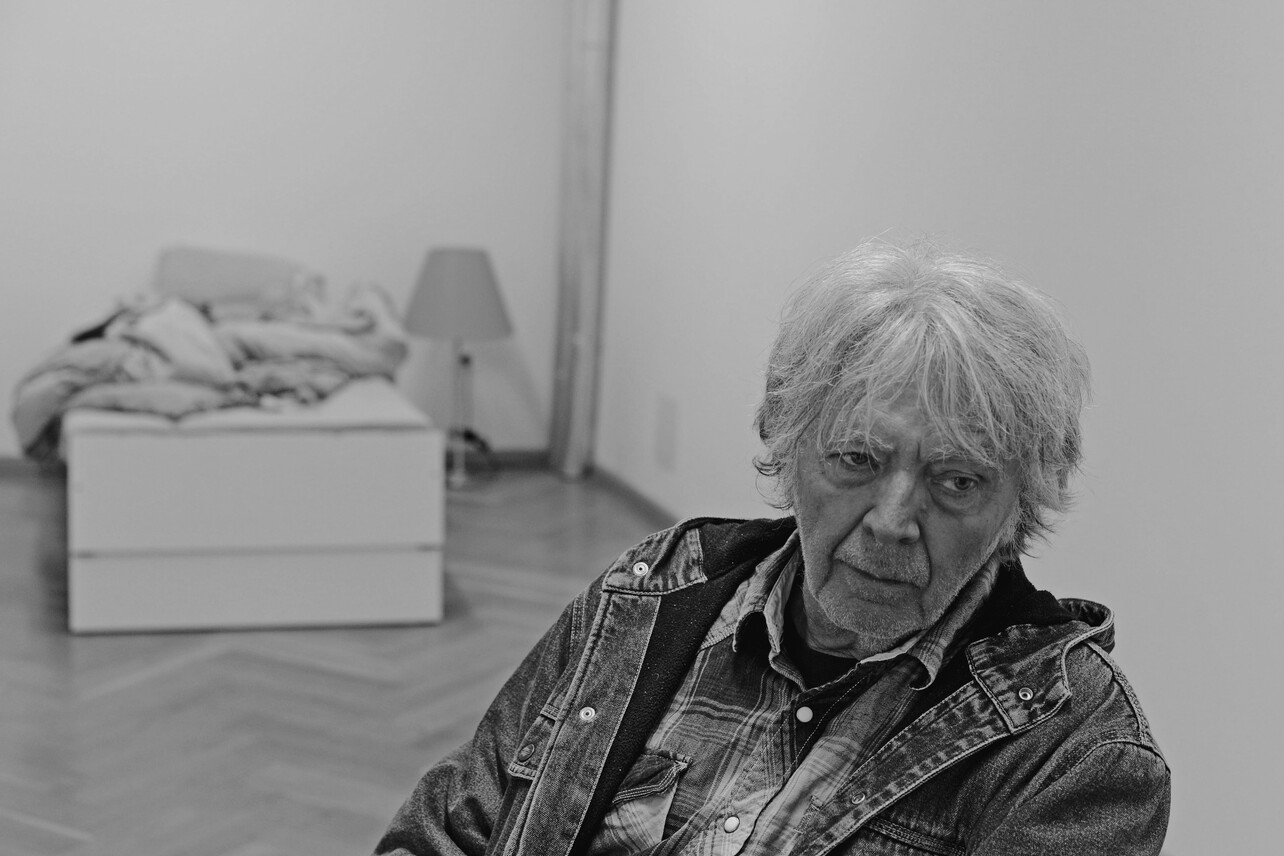

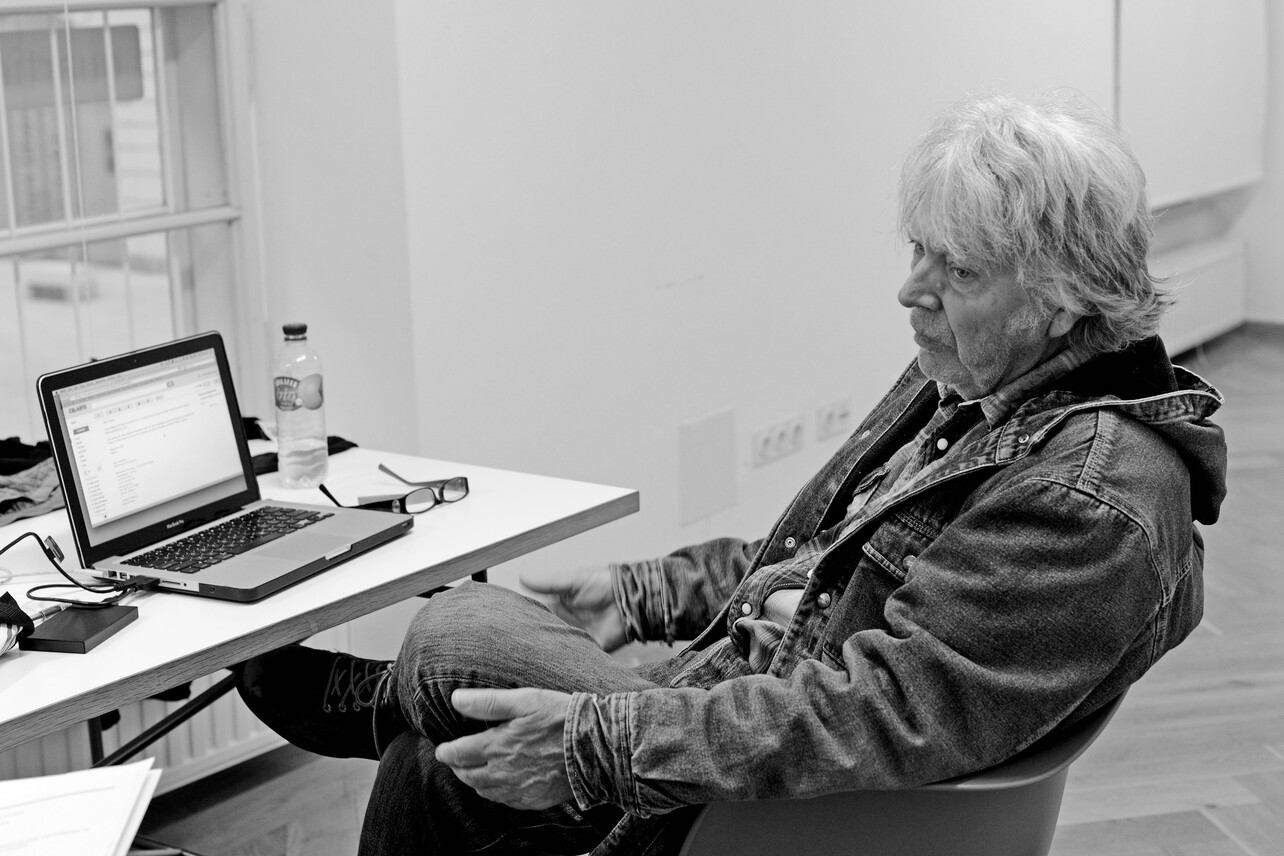

Artist-in-Residence James Benning in conversation with Margit Mössmer

The sounds you recorded in the Natural History Museum will be presented in the TONSPUR_passage under the title INFINITE DISPLACEMENT. What will we hear?

I made an hour long recording at the Natural History Museum where I had full access to the building. I was able to get very close to the top of the dome at the museum’s entrance. The idea was to displace the sounds from one museum space to another, in this case to the TONSPUR_passage at MuseumsQuartier. It’s both an extension and a conversation. I’m hoping to question the definition of art itself, to expand it. The work is a gesture to connect the two museums, connect the dots between the spaces. It’s a simple displacement of the sound that I recorded moving it 153 meters southwest and dropped it down 43 meters. It’s a cacophony of sounds that for me becomes music. Presented with the sound are seven photographs of digits, the first seven digits of π, one of the most important number in mathematics. Here I’m trying to connect mathematics to natural history and to art.

Do you see yourself as a sound artist or as a filmmaker?

I work in film the most, but never within the rather narrow film language of the dominate cinema. I always try to find a new language that comes from within, that is, from within the problem I am trying to solve. People call me a filmmaker, but I don’t really think I am, I’m really a conceptual artist.

In the movie DOUBLE PLAY, which is a portrait of you and filmmaker Richard Linklater, and was shown at this year’s Viennale you say that you never liked films.

I’m certainly not a cinephile. I mean there are a lot of good films, but I don’t like good films, I find it hard to engage with them intellectually, they are too self-satisfying; I don’t have to think much beyond what they are saying. I like things that are not quite so conclusive, things that stimulate me on a different level.

You refer to the manipulation of narrative film.

All film language is manipulation. Turning on a camera and making a frame already is manipulation.

It starts there.

It’s an edit, I’m always interested in what’s outside the frame.

Do you think that such categories as truth or lie determine cinema and film?

We live in a world that is untruthful, just look at any of our political systems. They are all pretty much motivated by greed, doing things for the wrong reasons. So what truth is, I don’t know, I wish we could have truth and justice.

We can’t even picture it.

It’s easier to lie. As you know, Godard said cinema was truth 24 times-per-second, and then Jean-Pierre Gorin later said, video is a lie 29,98 times a second, but for me it was always a lie, it’s just easier to lie in the new digital world, in analogue it was harder. However, you can still make films about how you feel. And that’s true. So even if you manipulate by juxtaposing different sounds, images; it still can be the truth about how you feel.

In your films 13 LAKES or 10 SKIES you made a quite radical decision letting duration play out its meaning.

That’s a good example. 13 LAKES is slightly manipulated. The manipulations I made in this film served to help reconstruct the experience that I had when I was there. I would for sure remove the sound of a jet plane that happened to come over, if indeed that sound was an unusual occurrence. If I had left it in, it would have been less the truth. This film is about my personal experience, it asks the question what was I thinking when I was there, and what would you have been thinking if you had been there. I wanted to show how monumental those lakes are and how strong the environment is. We’ll kill ourselves before we kill the planet, but I think it’s pretty clear that we’re destroying the system that supports us, our environment. For me I am sure that humans will be the next dominant species to disappear.

You say that the present is just a point, it has no dimensions, which is why you’re not interested in the present but in the future and past. However, when you talk about this "personal experience", it’s all about (bygone) presence, isn’t it?

Presence for me is hard to understand. We see it in such small terms, but we’re only here for such a short period of time. When you’re young time goes by slowly. When you’re 20 a year is a twentieth of your life, when you’re 80 a year is an eightieth of your life. So a year keeps getting smaller, because you always compare it with the time you have already lived. Compared to all of time, we are here only for a moment.

Presence is not important to you.

We are always in the presence, but the presence doesn’t exist. When I talk to you, you can only understand my sentence through memory. A blinking light doesn’t blink. It’s either on or off. The only reason we say it’s blinking is because we remember that it was on, went it is off, and off when it is on.

It’s the same with film. We need the picture before and after to get the picture in the middle.

We couldn’t even see movement if it wasn’t for memory.

How important is coincidence to you and your work?

When I was a kid I was encouraged to be adventurous, because I grew up at a time when parents allowed their children to wander off not worrying about losing them. I was allowed a great amount of freedom and I was clever enough not to do something stupid to lose that freedom. I was interested in observing and learning from new experiences and I loved to explore new parts of the city. It didn’t occurred to me then, but now it seems to me so important to actually understand that learning takes time and it can be fun and that you learn a lot from observing. If you question your old experiences when having new ones, it gives you the basis to understand both the old and the new. You don’t reinforce prejudice that way. I grew up in a very racist society. Poor white against poor black, we hated each other. If I would have viewed the rest of my life with that kind of prejudice I would never had grown. But by having other more enlightening experiences, I was able to rid myself of most of that ugliness.

And those new experiences sometimes happen just coincidentally?

Yes, of course, and sometimes they can be beautiful. In my very first long film 11 x 14, I was filming at the airport in Chicago and I waited for the sun to be right so that when the plane would land it would land right over my camera while its shadow would come from below. So you would have these two movements. I waited for an hour or so, on a street with a parking lot where there was hardly any traffic. When the plane came two rental trucks came parallel to each other, stopped and then they both turned left at the same time. It completely steals your eye. As soon as they leave the frame the plane and the shadow comes through. People said to me “Oh you were lucky…” I mean yeah it was luck, but if you film long enough eventually fortuities do happen.

You have to be patient.

Yeah, patience.

Are you impatient sometimes?

I am very impatient. That’s why I make these patient films. I was filming trains in Milwaukee with a friend one day and he couldn’t believe how nervous I was waiting for the train.

But you live very quietly.

I do. But I live a couple of lives. I teach, half the time I live in the mountains and I travel a lot. Teaching is very social and when I travel I meet lots and lots of people. I really enjoy getting back home to the mountains to decompress.

If you had the chance to make a film in Vienna, which location – I suppose you would only need one – would you choose?

Well I already got the chance to film in the Natural History Museum. To get access to that building was kind of a once in a lifetime experience. The film has little movement, just two people accidently walking into the frame, and one time some air is blowing from the air conditioning, you can see a sign tag on one of the stuffed animals moving slightly, but that’s it. However, the suggestion of movement is really great in the film because every room has its own ambient presence. Through the sound you can feel this constant movement. But as to another place to film, I’m very interested in this graveyard that is outside in that industrial area, where dead bodies have been washed up from the river.

The Graveyard of the Nameless

Yes, and I’m sure there are a lot more interesting locations in Vienna. I mean, probably it would be hard to do something in the first district, although, maybe I would film in Starbucks.

A film called ONE HOUR LOGO.

That’s good.

James Benning was Artist-in-Residence at Q21/MQ in November 2013. He was recommended by TONSPUR Kunstverein Wien.

TONSPUR 60 at TONSPUR_passage at MuseumsQuartier Wien

James Benning [USA]*

Infinite Displacement, 2013

8-channel sound installation, 7-part series of images

Length 60.00 min

Sound recording by James Benning

Thanks to neugerriemschneider, Berlin, Naturhistorisches Museum Wien,

Vienna Art Week, Videonale Bonn

*44th TONSPUR-Artist-in-Residence at quartier21/MQ

Interview: Margit Mössmer