Noémie Marsily on maternity, vulnerability and creativity

An interview with MQ Artist-in-Residence Noémie Marsily.

Virginia Woolf wrote that, "A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction." It relates to women's intellectual potential, and the outsized influence of men being due to a lack of opportunity rather than a lack of talent inherent in the opposite sex. At the intersection of art and politics, the Tricky Women/Tricky Realities film festival rewrites a film history that privileges the contributions of men. They create opportunities for film production, exhibition, criticism and distribution for female and gender diverse artists, resulting in an ecosystem of moving images that challenge the hegemony of patriarchal storytelling. This brings Belgian artist Noémie Marsily to the MuseumsQuartier, to a room of her own. She will reside here for three months as Artist-in-Residence.

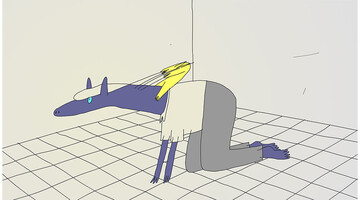

The jury responsible for her scholarship said of her latest film, Ce qui bouge est vivant (Whatever Moves Is Alive, 2022), “The construction and deconstruction of the personality of a mother is presented as a constant flow of gaining and losing, deep love and dependency. Intriguing is the minimalistic use of the drawing lines and its rough style, hectic like a very busy life of a mother with a small child.”

It´s particularly pronounced in your earlier films, but the character design has this child-like quality, then these characters are deployed in increasingly violent and absurd situations. What draws you towards these juxtapositions? Between innocence and idiosyncrasy?

I like to bring absurdity to things. I do it very spontaneously and in an intuitive way, which is similar to how I draw. Even if I’m now 40 years old, I can still relate to the child that I was. I can see things like she did. When I build stories or drawings, I’m interested in finding a balance between naivety and life's complexities. This interests me in terms of the graphics, but also the narration. When you dramatise something a little bit absurd or creepy, in a childish way of drawing, it yields a confrontation. A rupture between how something is and how it’s supposed to be.

You said you can relate to the child that you were, how has that changed now that you´ve had a child?

It’s part of what I was trying to say in my last film, Whatever moves is alive. When I look at her, I connect to myself when I was her age and the relationship I had with my mother back then. I have to be both now, mother and child. It's fascinating to watch someone grow up and become a person. To see them discovering everything for the first time and building a relationship with them. I relate to childhood through her, while still having to be a responsible adult. It’s interesting.

How do you see your latest film, relative to all of the other films that came before? It looks like a bit of a departure, stylistically and in terms of the story. What was different for you?

The way I made the film was different because I didn’t write a story or use a storyboard, it comes from notes in my diaries and sketch books that I started to animate in an impressionist way. I tried to express something that I didn’t fully understand, at least at first. It’s a self-portrait, but I don’t think I’ll tell these sorts of stories in that format again. It’s less confronting in a graphic novel, because there’s distance between yourself and your audience. I’m a reserved kind of person and having such intimate parts of your life projected on a screen in front of so many people requires a kind of courage. It was the first time it was really obvious that I was talking about myself. When I watch it with an audience, it's too intense. I'm like, “Oh, why? Why did I show that to them?!” Whatever moves is alive was a graphic experience and the most introspective film I’ve made. I just went through the process and the film is the result.

How would you describe the relationship between your personal life and your creative output?

I think you always bring things you’ve experienced into the stories you create, but Whatever moves is alive was the first time I really said to myself, “Okay, there is something here I want to express and it's really personal.” It’s complicated.

The word that's used on your MQ profile is autofiction, so an autobiographical experience that’s fictionalised and rendered in a different way, or translated into a different context.

Yes, that’s what I’m trying to do now. To find a balance between fiction and nonfiction. The project I'm working on now uses some experiences I’ve had, but I want to write a story around it and turn it into fiction. Autofiction is a vehicle to tell my story, in any way I want. To amuse myself, to create something funny with total freedom in the narration.

During your residency at MQ, you’ve said that you have many ideas that you need to write down and organize in order to find the best formal approach, and the result will either be a graphic novel or an animated film. What factors inform this decision?

Whatever moves is alive had to be an animated film, because of the movement. It’s a film about stillness in motion, when you’re stuck in a world that’s accelerating around you. The child is running but the mother is more like the slug. Not paralysed, but barely moving. This can be scary because something that doesn’t move at all is dead. But, even if progress is slow, it’s still progress. I was fascinated by that idea and found it reassuring.

Graphic novels allow you to tell longer stories, with a smaller team and budget. You can develop sound and dialogue in ways that can’t be translated into film. I’m using my residency at MQ to research phylactery, to experiment with sound in graphics. One of the subjects I want to develop is about communication between people, and language without words. What kinds of connections can be made, how can people express themselves, in voices without sound? I want to find a graphic language for this.

The relationship with the reader of a book is very different. Time has a different rhythm, readers can open and close a book at any time to reflect, it’s not projected in front of them. Graphic novels ask more of their readers because they have to fill the gaps between the images. They have to build the story with you, it is a co-construction. Film still requires audiences to make sense of the images you give them, but the director imposes the rhythm. The film starts, they watch it and then it’s over. It’s a completely different experience.

Your next piece will be an autofictional romantic comedy about a 40-year-old neuro-atypical single mother who recently discovered that she is a mermaid. What made you gravitate towards mermaids?

It’s a character that’s appeared in my diaries and sketch books for a long time now, like an alter ego in the shape of a mermaid. I didn't really know where it came from, but I feel like it’s a metaphor for feeling like a stranger in the human world. Trying to fit in, but not wanting to lose yourself. I’m working on that and finding a way to use that metaphor, to build a character and turn it into fiction.

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/b/d/csm_1.Transit_d20bb9deb2.jpg)